- Home

- Brian Lumley

Harry and the Pirates_and Other Tales from the Lost Years Page 3

Harry and the Pirates_and Other Tales from the Lost Years Read online

Page 3

“No, I don’t think so,” said Harry, standing up and accepting the drink that Jimmy handed him. “I’ll drink this, and then I think I’ll go for a walk—towards Hazeldene, maybe? Get some fresh air into my lungs, see if I can shake off this dull sloth or lethargy or whatever it is.” He took a long pull at his soft drink, almost finishing it in one go.

“Well, you’ll know best.” Jimmy shrugged. “You’ll be going on your own, though. There are a few jobs around the house I’ve been meaning to get done.”

“In which case I’ll see you when I see you,” said Harry as he handed his friend his almost empty glass, then stretched and grimaced before heading for the garden gate.

As Harry opened the gate, Jimmy’s frown displayed his continuing concern. “Are you sure you’re okay?”

“Absolutely,” said the other. “You’ll see. By tonight I’ll be my old self again and full of the devil.”

Finally Jimmy laughed, and said, “Full of the devil? Okay, but if you don’t get too full, maybe later on tonight we’ll top up with Old Nick down at the pub! That’s if you’re up to it.”

“Well, maybe,” said Harry. “We’ll see.” With which he went through the gate into a lane lined with a hedge, and headed for a stile that climbed over and down onto a narrow path. The path led off into knee-deep, grassy meadows with hilly ground rising beyond. That way, maybe two miles distant, lay Hazeldene’s forested valley, which was where this other—but this other what? This metaphysical interference maybe, or mental static?—this other “sound” anyway, seemed to have its origin. But if only it wasn’t so hard to pin down, so very faint!

Unnaturally faint, when considering its human origin! Even as faint, and indeed fainter, than massed dead-ant hysteria or deceased-fly musings. But what sort of communication could this possibly be? Which was exactly what the Necroscope intended to discover, and ASAP. More especially so because he knew instinctively that however remote or suppressed its source, this was a concerted cry of horror, which to him was the same as an SOS: a cry or cries for help.

But an SOS from the grave? Now what could the dead have to fear? A question which only the Necroscope could answer. And in fact he knew that there were indeed things that the dead should fear, for he had met up with several of them before. . . .

The sun blazed down, and even under the wide brim of his floppy hat Harry felt its heat. Using a handkerchief to mop sweat from the back of his neck, he sought respite on a bench in the shade of a flowering elder. Having crossed the fields to the high back road, he could now look down across Harden to the landmark viaduct and the North Sea that sprawled beyond. The sea, once grey from coal-mine spoil, was bluer than Harry had seen it in a long time; but then he hadn’t been back this way since . . . how long? Last summer, perhaps? The one before that? In any case, he knew the blue was simply the reflection of a mainly cloudless sky.

The western horizon, on the other hand, saw that same blue sky merging with a bank of green: the rim of the densely wooded valley of Hazeldene, which was the Necroscope’s destination and the source of those infinitely faint whispers that continued to sound in his mind. For the moment he tried to ignore the apparent desperation, the subdued terror in those whispers. What use listening to the unknown dead ones in question when he couldn’t talk to them? He had tried that already but they didn’t seem to hear him. Harry sensed—he “knew,” by virtue of his fantastic intuitive talent—that they were close, only a few miles away; and yet they sounded as distant as could be. It was the strangest thing and quite beyond every previous experience. . . .

The back road, hedged and narrow, had grass verges. Apart from a police car parked some fifty yards away half-on, half-off the road, where three-bar fencing broke the hedge’s monotony, there were no other vehicles in sight. Harry assumed that the patrolman was taking a break nearby, perhaps relieving himself behind the hedge. What else would a policeman be doing out here in the open countryside, where there was little or nothing to police?

Moving away from the Necroscope towards near-distant Blackhill Colliery, a young man and his girl ambled arm in arm. From the opposite direction, closing with the couple, a pair of teenage colliery youths—their flat caps jutting and their hands thrust deep in their trouser pockets—slouched along the grass verge. Harry, where he enjoyed for the moment the elder’s shade and a soft salt breeze wafting in off the sea, gradually became aware of the coarse sniggering of these two youths as they drew level with the young couple; but suddenly he found himself listening far more intently, no longer to the faint and mysterious murmurings of the dead but to the lewd, uncouth comments of the living—in the shape of this pair of louts.

Just a moment ago the largest and ugliest of these village types had taken his cap off and addressed the young couple with the words: “Oh, hello there! Lovely day for a country walk, eh? Out for a sneaky shag in the long grass, are we? Eh? Eh?”

And his smaller, stockier companion had grinned and added: “Can we watch? I mean, maybe we could help you out a bit if you get, er, stuck or something?”

“Why you dirty—!” Outraged, the young man let go his companion’s arm, placed himself in front of her, and faced the pair of troublemakers. It was immediately apparent, however, that he would be no match for them. He was tall but spindly, and by his looks and actions—his rapidly reddening face and clumsy, uncertain movements—by no means a fighter. As for the thugs:

They had received the response they’d been looking for and their hands were out of their pockets now, clenched into fists. The biggest of the two had thrust himself forward, grabbed hold of and bunched up his potential victim’s shirt.

“What’s that you say?” he snarled. “Did you call us dirty, you soft-looking prat? I mean, did you call me dirty? See, this is just us having a bit of fun—fuckhead! We wouldn’t want to fuck your stupid tart. Personally I’d rather fuck you—except you’d probably split in two! What do you say to that? Eh? Eh?”

By which time the Necroscope was on his feet and half-way across the distance between the bench and this ugly and totally unanticipated confrontation. As he went, however, he found time to speak to a friend of his in the cemetery near his old school in the village:

Sergeant, are you getting any of this?

All of it, Harry, through your eyes! Sergeant replied, and the Necroscope sensed a grim however incorporeal nod. You could maybe use some help, but from the looks of these two bully boys only a very little help. And by the way: good day to you, too!

Er, I was going to come and look you up, said Harry truthfully if belatedly. In fact there are several old friends close by who I’ve yet to talk to.

It’s okay, no sweat, Sergeant answered, and the Necroscope sensed the grin he’d be wearing if he still had a face on which to wear it. But hey, do you want me to handle this? If so you’d better let me in.

Harry opened his mind to him—opened it all the way—and at once felt the other’s presence like a mild electric shock in his body and all his limbs. By which time he had almost reached the four people where they faced each other off.

The smallest of the two thugs had become aware of his approach and said, “Hey, Jim, will you look what’s here? Some kind of twat in a hat!” With which he burst into sniggering laughter and did a funny little foot-stamping jig. “I mean, just look at this bloke—his flashing eyes and hard-man scowl! God, I could die laughing! Talk about the Caped Crusader to the rescue? Well in this bloke’s case it’s the floppy-hatted twat!”

“Eh?” said the slack-faced larger thug, releasing his grip on the young man’s shirt and turning to look at Harry with dull narrow eyes. “What did you say, Kev?” Jim, who obviously wasn’t nearly as clever as Kevin, focussed his eyes on Harry for a few seconds before bursting into guttural laughter like his smaller companion. And: “Oh yeah, I get it!” he said. “A twat in a twat hat, eh? Right?”

By now the Necroscope was within arm’s length of the group. As he came to a halt and without preamble, he said, “You have a c

hoice, you two: to either get on your way or to get hurt, it’s up to you. So what’s it going to be?”

“Eh?” said Jim—his favourite comment, apparently—as a disbelieving frown furrowed his forehead.

“Were you born thick, you fellows?” said Harry, grinning a deliberately caustic grin that he kept in reserve for occasions like this. “Or did it take a lot of practice? Maybe you studied for it in reform school, right?”

As it happened, however, they weren’t quite that thick and the Necroscope knew from the way their jaws dropped that he had beaten these thugs at their own game, taunted them beyond endurance.

Jim and Kevin glanced at each other furtively, and yet in a fashion familiar to them; for they had known similar situations before. And as an unspoken message passed between them, then as one man they turned on Harry and lashed out at him with knobbly fists—which was an enormous mistake. For of course “Sergeant” Graham Lane was now a part of Harry, mind and body.

The Necroscope’s dead friend, an ex-Army physical training instructor and a very hard man in his time—a man who had left the Army early to become a PTI for pre-teen schoolchildren, and who had died in an accident when Harry was just such a child—had loaned his martial arts expertise to Harry on several occasions in the past and was pleased and eager to be able to do so again. Since the Necroscope was his only contact with the world of the living, however, this was hardly surprising; and just as Sergeant was into Harry’s mind, so the Necroscope was into his:

Sergeant! he now cautioned the dead man. Hurt them, by all means, but try not to break any bones. Please remember that I’m the one who might have to explain it if you do. . . . Oops!

That last because Sergeant didn’t appear to be listening.

Leaning back from the wildly flailing arms of the pair of bullies, Harry’s supple body turned side-on and bent at ninety degrees at the waist away from his opponents. At the same time his right foot came off the ground, his heel stiffening into a club that his piston leg drove into the larger thug’s genitals.

“Ow!” that one at once grunted, gentling his groin in both hands, dropping to his knees, and slowly toppling over sideways to the grass verge. And again, with feeling: “Ow!” as he curled into a ball there.

Sergeant! Harry warned. But too late because his body—as of its own volition, but in fact of Sergeant’s—had spun like a top through a full three hundred and sixty degrees, his right leg extended and rising into a higher orbit. And once again his heel had come into crippling contact with soft flesh, this time in the form of Kevin’s nose.

Blood and snot flew; as did the astonished, agonised thug, his arms windmilling as he landed on his backside in a drainage ditch between the verge and the hedge.

With both thugs immobilised and sobbing their misery, just as quickly as that it appeared to be over. But—

“Well now!” said a calm and mature, unfamiliar but plainly authoritative voice from behind the Necroscope, just as he felt himself beginning to relax. “And what have we here?”

Harry turned to face a uniformed constable in shirt-sleeve order. Despite that he appeared to be in his late thirties, the neatly-clipped sideboards coming down under his policeman’s hat were prematurely grey; his eyes were also grey and perhaps more than a little cynical, as was his thin, tight-lipped mouth. Yet paradoxically, in a way that was hard-to-define, the aura given off by the man behind those eyes and that mouth seemed far less cynical than careworn and world-weary. Also—looking oddly out of place, as did the man himself—a pair of binoculars dangled from a leather strap worn around his neck.

“Er, I—” Harry began, only to be cut off by the girl he had rescued from an embarrassing, even threatening situation:

“This man helped us out when things were beginning to look bad,” she explained. “And as for these two—” she indicated the pair who were still on the ground, “—they were acting like . . . like animals! They well deserved what they got!”

Her young man added: “I was . . . well, I was taken by surprise, else I might have been of some help. But—”

“But as it happened,” the policeman cut him off, “I saw it all and this gent here—” he indicated Harry, “—didn’t appear to need any help, now did he?” Taking out his notebook, he then spoke to Harry. “Might I ask who you are, sir?”

“My name is Keogh—Harry Keogh,” the Necroscope replied. “I’m from Edinburgh, staying with a friend in Harden.”

The policeman made as if to write in his book, changed his mind, and tucked it away again in the shirt pocket that held his whistle. “You don’t have much of a Scottish accent,” he said.

“I was brought up in these parts,” said Harry. “I attended school in Harden.” And after a moment’s pause: “Look, I’m sorry if I’m in the wrong here, but I heard the filthy language these two louts were using and it seemed to me that this young couple were in trouble. Also, when I approached, I too was threatened! So it appears to me your time would be better employed speaking to these thugs rather than the ones they were insulting.”

The other smiled a tight smile. “No need to speak to these two,” he said. “I know them well enough. Work-shy hooligans, the pair of them; nothing they like better than causing trouble for decent, hardworking people.” He scowled at the thugs where they were beginning to crawl away along the grass verge, then asked: “Do you want to bring charges, any of you?”

Feeling relieved, Harry shook his head. “I’m not sure it’s necessary. I think they’ve learned a lesson.”

And the young man asked, “What do you suggest, Constable?”

The policeman chewed his lip, thought it over, and finally said, “I think you should let it go. Twenty years ago it’s possible I might have wheeled them down to the station and let them spend a night in the cells. They’d get out tomorrow each with a black eye, a fat lip, and a few bruises, and that would be that. Today, however, it doesn’t work like that. The do-gooders would be yelling about police brutality and all that rubbish, and I’d be the one to end up in the dock. And—” he turned to stare at Harry, “—so would you, Mr. Keogh.”

The louts had got to their feet and were limping painfully away. The constable called after them, “You two: I know you, Jim Carter, Kevin Quillern, and I saw what happened here. Any loose talk, accusation, complaints from you two, you’ll answer for it in court, believe me. So consider yourselves fortunate, and now bugger off and quick about it!” Far less threateningly, he then turned to Harry and the young couple, saying, “Do please excuse the bad language, though it wasn’t nearly as bad as theirs!”

“Can we get on our way now?” the young man asked.

“After you’ve told me your names,” said the policeman. “In case it later turns out that I need them.”

“Alex Munroe,” the other replied. “I’m from Easingham. And this is my fiancée, Gloria Stafford, also from Easingham.”

“Good enough,” the policeman nodded. “You can go. I’m only sorry you’ve been troubled.”

The girl turned to Harry. “You’re very kind and brave, Mr. Keogh, to have stepped in like that. Thank you very much.”

“Er, you’re welcome,” said the Necroscope. “But really, it wasn’t much. I mean, I didn’t have a lot to do.”

Barely anything, in fact, said Sergeant, receding from his mind and body.

As the young couple moved off, the constable said, “Do you mind telling me where you learned to do that—your karate, or whatever it was?”

Harry had to think fast, but why tell lies? “My instructor was an ex-Army PTI,” he said. “He died in an accident some time ago.” And giving Sergeant his due: “He was a Black Belt in some disciplines and exceptional in many more. As for my own skills: well, for what it’s worth, they’re all down to my knowing him.”

“He obviously taught you well,” said the other. “I wish I was half as good! What were you doing up here?”

“Just walking,” Harry answered, with a shrug. “Heading for Hazeldene. A bit o

f nostalgia, perhaps? I used to play there as a child.”

As they set off back towards the parked car, the constable volunteered, “I’m Jack Forester—the lesser half of local law enforcement. The greater half is the senior officer I share the workload with. Actually, today is my day off—but I had nothing better to do.”

And Harry thought, What, no home life? Nothing outside of your work? Now that is dedication! Or is it something else? But he nodded and out loud said, “I can remember the police station being close to my old school—Harden’s Secondary Modern Boy’s—down towards the viaduct.”

“Yes, and the school is still there,” said Forester. “But the police station is only a police post now. We still get some petty crime—sometimes not quite so petty—but when it’s big stuff the detectives or reinforcements drive in from Hartlepool or Sunderland. It’s all down to communications really. You see, Harry, in villages like Harden the computer age has put many of us out of business, and I suppose I’m fortunate to still have a job! . . . I take it it’s okay to call you Harry?”

“By all means,” said the Necroscope. And more boldly: “May I ask why you were out here, er, Jack? I mean, with your binoculars and all?”

Glancing at him through narrowed eyes, Forester said, “Oh, I was just keeping my eyes on things, you know . . . ?” And quickly changing the subject: “Look, I’m taking the old farm track past Hazeldene right now, so if you’d like a ride . . . ?”

Harry shook his head. “Thanks, but no thanks. I think I’ll enjoy the walk.” Actually, and if he wanted to, he could get to his destination long before the policeman, but that wasn’t something he was about to mention.

“Suit yourself,” said Forester, getting into his car. “And let’s hope you have no more trouble from local louts, eh? But I should warn you, these days we have more than our fair share of them. Plenty of crazy people, too!”

Mad Moon of Dreams

Mad Moon of Dreams Psychosphere

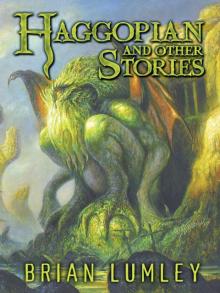

Psychosphere Haggopian and Other Stories

Haggopian and Other Stories Resurgence_The Lost Years_Volume Two

Resurgence_The Lost Years_Volume Two Necroscope: Harry and the Pirates: And Other Tales From the Lost Years

Necroscope: Harry and the Pirates: And Other Tales From the Lost Years Necroscope®

Necroscope® Dreamlands 5: Questers for Kuranes: Two Tales of Hero and Eldin

Dreamlands 5: Questers for Kuranes: Two Tales of Hero and Eldin The Taint and Other Novellas: Best Mythos Tales Volume 1

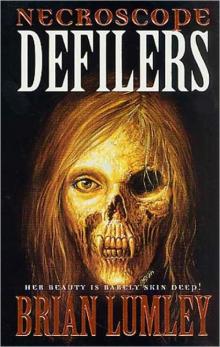

The Taint and Other Novellas: Best Mythos Tales Volume 1 Necroscope: Defilers

Necroscope: Defilers Beneath the Moors and Darker Places

Beneath the Moors and Darker Places The Fly-By-Nights

The Fly-By-Nights Khai of Khem

Khai of Khem Ship of Dreams

Ship of Dreams The Nonesuch and Others

The Nonesuch and Others Blood Brothers

Blood Brothers Necroscope

Necroscope The Burrowers Beneath

The Burrowers Beneath Bloodwars

Bloodwars No Sharks in the Med and Other Stories

No Sharks in the Med and Other Stories The House of Doors - 01

The House of Doors - 01 Screaming Science Fiction

Screaming Science Fiction Necroscope III: The Source

Necroscope III: The Source Vampire World I: Blood Brothers

Vampire World I: Blood Brothers Iced on Aran

Iced on Aran Necroscope: Invaders

Necroscope: Invaders Necroscope: The Lost Years

Necroscope: The Lost Years Return of the Deep Ones: And Other Mythos Tales

Return of the Deep Ones: And Other Mythos Tales Necroscope V: Deadspawn

Necroscope V: Deadspawn Titus Crow, Volume 3: In the Moons of Borea, Elysia

Titus Crow, Volume 3: In the Moons of Borea, Elysia Hero of Dreams

Hero of Dreams Necroscope IV: Deadspeak

Necroscope IV: Deadspeak The Last Aerie

The Last Aerie The Second Wish and Other Exhalations

The Second Wish and Other Exhalations Necroscope: The Touch

Necroscope: The Touch Necroscope: The Plague-Bearer

Necroscope: The Plague-Bearer Necroscope: Avengers

Necroscope: Avengers Necroscope II: Wamphyri

Necroscope II: Wamphyri Necroscope II_Vamphyri!

Necroscope II_Vamphyri! A Coven of Vampires

A Coven of Vampires Spawn of the Winds

Spawn of the Winds Sorcery in Shad

Sorcery in Shad Deadspawn

Deadspawn Necroscope V: Deadspawn n-5

Necroscope V: Deadspawn n-5 Necroscope: Invaders e-1

Necroscope: Invaders e-1![Beneath the Moors and Darker Places [SSC] Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/beneath_the_moors_and_darker_places_ssc_preview.jpg) Beneath the Moors and Darker Places [SSC]

Beneath the Moors and Darker Places [SSC] Demogorgon

Demogorgon Harry and the Pirates_and Other Tales from the Lost Years

Harry and the Pirates_and Other Tales from the Lost Years Necroscope IV: Deadspeak n-4

Necroscope IV: Deadspeak n-4 Deadspeak

Deadspeak The Taint and Other Novellas

The Taint and Other Novellas Blood Brothers vw-1

Blood Brothers vw-1 The Source n-3

The Source n-3 In the Moons of Borea

In the Moons of Borea Avengers

Avengers Necroscope n-1

Necroscope n-1 Vamphyri!

Vamphyri! Questers for Kuranes: Two Tales of Hero and Eldin

Questers for Kuranes: Two Tales of Hero and Eldin Necroscope II: Wamphyri! n-2

Necroscope II: Wamphyri! n-2 The Source

The Source Elysia

Elysia The Plague-Bearer

The Plague-Bearer The Touch

The Touch Invaders

Invaders Necroscope 4: Deadspeak

Necroscope 4: Deadspeak Compleat Crow

Compleat Crow The Mobius Murders

The Mobius Murders Defilers

Defilers