- Home

- Brian Lumley

Deadspeak Page 20

Deadspeak Read online

Page 20

In Edinburgh, Darcy Clarke and Norman Wellesley were waiting in the road outside the sweeping terraced facade of Georgian houses where Sandra had her flat. They were in the back of Wellesley’s car, parked up, with two other branch men; but as she came into view round a corner they got out of the car and met her at the door of the house. She had the ground-floor flat; without speaking, she ushered them inside.

“Nice to see you again, Miss Markham.” Wellesley nodded, taking a seat.

Clarke was less formal. “How are things, Sandra?” He forced a smile.

She caught a brief glimpse of his mind and it was all worry and uncertainty. But nothing specific. Harry was in it somewhere, though, be sure. Of course he was; why else would these two be here? She said, “Coffee?” and without waiting for their answer went into her kitchen alcove. Let them do the talking.

“We have time for a coffee, yes,” said Wellesley, in that oh-very-well, I-suppose-I-shall-have-to-accept way of his, as if it were his damned right! “But actually we’re pretty busy and won’t prolong our visit too much. So if we can get right to it: did you have plans to see Keogh tonight?”

Just like that … and “Keogh,” not Harry. Will you be in his bed, or he in yours? Wellesley was asking. Humping again tonight, are you?

There was something about this man that got Sandra’s back up. And the fact that his mind was a complete blank—not even radiating the faintest glow—was only a small part of it. She glanced back at him from the alcove with eyes that were cold where they met his. “He said he might call me,” she answered unemotionally.

“It’s just that we’d prefer it if you don’t see him tonight, Sandra,” Clarke hurriedly put in before Wellesley could use that blunt instrument he called a tongue again. “I mean, we plan on seeing him ourselves. And we’d like to avoid, you know, any embarrassing confrontations?”

She didn’t know, really. But she brought them their coffee anyway and gave Darcy a smile. She’d always liked him. She didn’t like to see him uncomfortable in the presence of his boss. Their boss, though not for much longer. Not if things worked out as she hoped they would. “I see,” she said. “So what’s happening?”

“No need for you to concern yourself.” Wellesley was quick off the mark. “Just routine stuff. And, I’m afraid, confidential.”

And suddenly she was afraid, too … for Harry. More complications? Something to interfere with her own plans, which she hoped would be the best for him? It was on the tip of her tongue to tell them about the new developments, what she knew of them, but she held it back. There was that in their attitude—Wellesley’s, anyway—which warned that now wasn’t a good time. And anyway, it would all go in her end-of-month report, along with her resignation.

They all three finished their coffees in silence. And finally: “That’s it, then,” said Wellesley, standing up. “We won’t be seeing you!”—his idea of a smart remark! He nodded, offered her a twitchy half smile, and headed for the door. She saw them out, and Wellesley’s parting shot was, “So if he does, er, call you, do put him off, won’t you?”

She might have answered him in kind right there and then, but Clarke gave her arm a reassuring squeeze just above the elbow, as if saying: “It’s okay, I’ll be there.”

But why should Darcy be acting so concerned? She’d rarely seen him looking so on edge …

VII: Deadspeak

AFTER DROPPING SANDRA OFF IN BONNYRIG AND DURING the short drive home, Harry stopped at a newsagent’s and bought himself a pack of twenty cigarettes. He looked at his change but didn’t try to check it. It wouldn’t make any sense to him anyway. They could rip him off every time and he just wouldn’t know it.

That was the other thing Harry Jr. had done to him: he was now innumerate. No way he could use the Möbius Continuum if he couldn’t even calculate the change from a pack of cigarettes! Sandra saw to it that his bills were paid, or he’d probably get that wrong, too. What price his “instinctive mathematics” now, eh? The Möbius equations? What the hell were they? What had they looked like?

And again Harry wondered, Was it a dream? Was that all it had been? A fantasy? A figment of his own imagination? Oh, he remembered how it had been, all right; but as he’d tried to explain to Sandra, it was the way you remember a dream, or a book you read in childhood, fast fading now. Had he really, really, done all of those things? And if he had, did he really, really, want to be able to do them again? To talk to the teeming dead, and step through doors no one else guessed existed to travel swift as thought in the metaphysical Möbius Continuum?

Want it? Perhaps not, but what was there without it? What was he without it? Answer: Harry Keogh, nowhere man.

Back home he went into the garden and looked at the stones again:

They meant nothing to him. But still he fixed their meaningless legend in his mind. Then he brought the wheelbarrow, loaded it up, and wheeled the stones back to the wall where … he paused a moment and stood frowning, before wheeling them back up to the lawn again. And there he left them, in the wheelbarrow.

For if—just if—someone was trying to tell him something, well, why make things harder for them?

Indoors again, Harry climbed stairs and then ladders to the attic room which no one else suspected was there—that large, dusty room with its sloping rear window, naked light bulb hanging from a roof timber, and its rows and rows of bookshelves—which was now a shrine to his obsession, if the word “shrine” were at all applicable. And of course the books themselves. All the facts and the fictions were here, all the myths and legends, all the “conclusive condemnations” and “indisputable evidences” for or against, proving, disproving, or standing in the middle ground of Harry’s studies. The history, the lore, the very nature … of the vampire.

Which was in itself a grim joke, for how could anyone ever fully understand the nature of the vampire? And yet if any man could, then it was Harry Keogh.

But he hadn’t come here today to look again at his books or delve a little deeper into the miasma of times, lands, and legends long past. No, for he believed that time itself was well past for those things, for study and vain attempts at understanding. His dreams of red threads among the blue were immediate things, “now” things, and if he’d learned nothing else in his weird life, it was to trust in his dreams.

The Wamphyri have powers, Father!

An echo? A whisper? The scurry of mice? Or … a memory?

How long before they seek you out and find you?

No, he wasn’t here to look at his books this time. The time to study an enemy’s tactics is before the onslaught. Too late if he’s already come a-knocking at your door. Well, he hadn’t, not yet. But Harry had dreamed things, and he trusted his dreams.

He took down a piece of modern weaponry (yes, modern, though its design hadn’t changed much through sixteen centuries) from the wall and carried it to a table where he laid it down on newspapers preparatory to cleaning, oiling, and generally servicing the thing. There was this, and in the corner there a sickle whose semicircular blade gleamed like a razor, and that was all.

Strange weapons, these, against a force for blight and plague and devastation potentially greater than any of man’s thermonuclear toys. But right now they were the only weapons Harry had.

Better tend to them …

The afternoon passed without incident; why shouldn’t it? Years had passed without incident, within the parameters of the Harry Keogh mentality and identity. He spent most of the time considering his position (which was this: that he was no longer a Necroscope, that he no longer had access to the Möbius Continuum), and ways in which he might improve that position and recover his talents before they atrophied utterly.

It was possible—barely, Harry supposed, considering his innumeracy—that if he could speak to Möbius, then Möbius might be able to stabilize whatever mathematical gyro was now out of kilter in his head. Except first he must be able to speak to him, which was likewise out of the question. For of course Möbius had b

een dead for well over a hundred years, and Harry was forbidden to speak to the dead on penalty of mental agony.

He could not speak to the dead, but the dead might even now be looking at ways in which they could communicate with him. He suspected—no, he more than suspected, was sure—that he spoke to them in his dreams, even though he was forbidden to remember or act upon what they had told him. But still he was aware that warnings had been passed, even if he didn’t know what those warning were about.

One thing was certain, however: he knew that within himself and within every man, woman, and child on the surface of the globe, a blue thread unwound from the past and was even now spinning into the future of humanity, and that he had dreamed—or been warned—of red threads amidst the blue.

And apart from that—this inescapable mood or sensation of something impending, and something terrible—the rest of it was a Chinese puzzle with no solution, a maze with no exit, the square root of minus one, whose value may only be expressed in the abstract. Harry knew the latter for a fact, even if he no longer knew what it meant. And it was a puzzle he’d examined almost to distraction, a maze he’d explored to exhaustion, and an equation he hadn’t even attempted because like all mathematical concepts it simply wouldn’t read …

In the evening he sat and watched television, mainly for relaxation. He’d considered calling Sandra, and then hadn’t. There was something on her mind, too, he knew; and anyway, what right had he to draw her into … whatever this was, or whatever it might turn out to be? None.

So it went; evening drew towards night; Harry prepared for bed, only to sit dozing in his chair. The dish in his garden collected signals and unscrambled their pictures onto his screen. He started awake at the sound of applause and discovered an American chat-show host talking to a fat lady who had the most human, appealing eyes Harry could imagine. The show was called “Interesting People” or some such and Harry had watched it before. Usually it was anything but interesting; but now he caught the word “extrasensory” and sat up a little straighter. Naturally enough, he found ESP in all its forms entirely fascinating.

“So … let’s get this right,” the skeletally thin host said to the fat lady. “You went deaf when you were eighteen months old, and so never learned how to speak, right?”

“That’s right,” the fat lady answered, “but I do have this incredible memory, and obviously I’d heard a great many human conversations before I went deaf. Anyway, speech never developed in me, so I wasn’t only deaf but dumb, too. Then, three years ago, I got married. My husband is a technician in a recording studio. He took me in one day and I watched him working, and I suddenly made the connection between the oscillating sensors on his machinery and the voices and instrument sounds of the group he was recording.”

“Suddenly you got the idea of sound, right?”

“That’s correct.” The fat lady smiled, and continued, “Now, I had of course learned sign language or dactylol-ogy—which in my mind I’d called dumbspeak—and I also knew that some deaf people could carry on perfectly normal conversations, which I termed deafspeak. But I hadn’t tried it myself simply because I hadn’t understood sound! You see, my deafness was total, absolute. Sound didn’t exist—except in my memory!”

“And so you saw this hypnotist?”

“Indeed I did! It was hard but he was patient—and of course it mightn’t have been possible at all except he was able to use dumbspeak. So he hypnotised me and brought back all the conversations I’d heard as a baby. And when I woke up—”

“You could speak?”

“Exactly as you hear me now, yes!”

“The hell you say! Not only fully articulate but almost entirely without accent! Mrs. Zdzienicki, that’s a most fascinating story and you really are one of the most interrrresting people we’ve ever had on this show!”

The camera stayed on his thin, smiling face and he nodded his head in frenetic affirmation. “Yessiree! And now, let’s move on to—”

But Harry had already moved to switch off the set; and as the screen blinked out he saw how dark it had grown. Almost midnight, and the house temperature already falling as the timer cut power to the central heating system. It was time he was in bed …

… Or, maybe he’d watch just one more interview with one of these interrrresting people! He didn’t remember switching the set on again, but as its picture formed he was drawn in through the screen where he found Jack Garrulous or whatever his name was adrift in the Möbius Continuum.

“Welcome to the show, Harry!” said Jack. “And we just know we’re going to find you verrry interesting! Now, I’ve been sort of admiring this, er, place you’ve got here? What did you say it was called?” He held out his microphone for Harry to speak into.

“This is the Möbius Continuum, Jack,” said Harry, a little nervously, “and I’m not really supposed to be here.”

“The hell you say! But on this show anything goes, Harry. You’re on prime time, son, so don’t be shy!”

“Time?” Harry said. “But all time is prime, Jack. Is time what you’re interested in? Well, in that case, take a look in here.” And grabbing Garrulous by the elbow, he guided him through a future-time door.

“Interrrresting!” the other approved, as side by side they shot into the future, towards that far faint haze of blue which was the expansion of humanity through the three mundane dimensions of the space-time universe. “And what are these myriad blue threads, Harry?”

“The life threads of the human race,” Harry explained. “See over there? That one just this moment bursting into being, such a pure, shining blue that it’s almost blinding? That’s a newborn baby with a long, long way to go. And this one here, gradually fading and getting ready to blink out?” He lowered his voice in respect. “Well, that’s an old man about to die.”

“The hell—you—say!” said Jack Garrulous, awed. “But of course, you’d know all about that, now wouldn’t you, Harry? I mean, about death and such? For after all, aren’t you the one they call a necrowhatsit?”

“A Necroscope, yes.” Harry nodded. “Or at least I was.”

“And how’s that for a talent, folks?” Garrulous beamed with teeth like piano keys. “For Harry Keogh’s the man who talks to the dead! And he’s the only one they’ll talk back to—but in the nicest possible way! See, they kind of love him. So”—he turned back to Harry—“what do you call that sort of conversation, Harry? I mean, when you’re talking to dead folks? See, a little while ago we were speaking to this Mrs. Zdzienicki who told us all about dumbspeak and deafspeak and—”

“Deadspeak,” Harry cut him short.

“Deadspeak? Really? The hell … you … say! Well, if you haven’t been one of the most interrrr …” And he paused, squinting over Harry’s shoulder.

“Um?” said Harry.

“One last question, son,” said Garrulous urgently, his narrowing eyes fixed on something just outside Harry’s sphere of vision. “I mean, you told us about the blue life-threads sure enough, but what in all get out’s the meaning of a red one, eh?”

Harry’s head snapped round; wide-eyed, he stared; and saw a scarlet thread, even now angling in towards him! And:

“Vampire!” he yelled, rolling out of his armchair into the darkness of the room. And framed in the doorway leading back into the rest of the house, he saw the silhouette of what could only be one thing: that which he’d known was coming for him!

There was a small table beside his chair, which Harry had knocked flying. Groping in the darkness, his fingers found two things: a table lamp thrown to the floor and the weapon he’d worked on earlier in the day. The latter was loaded. Switching on the lamp, Harry went into a crouch behind his chair and brought up his gleaming metal crossbow into view—and saw that his worst nightmare had advanced into the room!

There was no denying the thing: the slate grey colour of its flesh, its gaping jaws and what they contained, its pointed ears and the high-collared cape which gave its skull and menacing features d

efinition. It was a vampire—of the comic-book variety! But even realising that this wasn’t the real thing (and he of all people should know), still Harry’s finger had tightened on the trigger.

It was all reaction. This body he’d trained to a peak of perfection was working just as he’d programmed it to work in a hundred simulations of this very situation. And despite the fact that he’d come immediately awake—and that he knew this thing in his room with him was a fraud—still his adrenaline was flowing and his heart pounding, and his weapon’s fifteen-inch hardwood bolt already in flight. It was only in the last split second that he’d tried to avert disaster by elevating the crossbow’s tiller up towards the ceiling. But that had been enough, barely.

Wellesley, seeing the crossbow in Harry’s hand, had blown froth through his plastic teeth in a gasp of terror and tned to back off. The bolt missed his right ear by a hair breadth, struck through the collar of his costume cape, and snatched him back against the wall. It buried itself deep in plaster and old brick and pinned him there.

He spat out his teeth and yelled, “Jesus Christ, you idiot, it’s me!” But this was as much for the benefit of Darcy Clarke, back there somewhere in the dark house, as for Harry Keogh. For even as he was shouting, Wellesley’s right hand reached inside the coat under his cape and grasped the grip of his issue 9-mm Browning. This was his main chance. Keogh had attacked him, just as he’d hoped he would. It was self-defence, that’s all.

Harry, taking no chances, had nocked his bow, snatched the auxiliary bolt from its clips under the tiller of his weapon, and placed it in the breech. In a sort of slow motion born of the speed of his own actions, he saw Wellesley’s arm straightening and coming up into the firing position; but he couldn’t believe the man would shoot him. Why? For what reason? Or perhaps Wellesley feared he was going to use the crossbow again. That must be it, yes. He dropped his weapon into the armchair’s well and threw up his arms.

But now Wellesley’s aim was unwavering, his eyes glinting, his knuckle turning white in the trigger guard of the automatic. And he actually grinned as he shouted, “Keogh, you madman—no! No!”

Mad Moon of Dreams

Mad Moon of Dreams Psychosphere

Psychosphere Haggopian and Other Stories

Haggopian and Other Stories Resurgence_The Lost Years_Volume Two

Resurgence_The Lost Years_Volume Two Necroscope: Harry and the Pirates: And Other Tales From the Lost Years

Necroscope: Harry and the Pirates: And Other Tales From the Lost Years Necroscope®

Necroscope® Dreamlands 5: Questers for Kuranes: Two Tales of Hero and Eldin

Dreamlands 5: Questers for Kuranes: Two Tales of Hero and Eldin The Taint and Other Novellas: Best Mythos Tales Volume 1

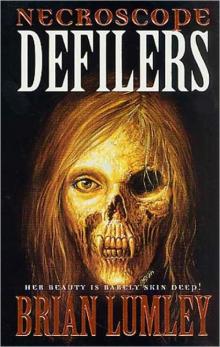

The Taint and Other Novellas: Best Mythos Tales Volume 1 Necroscope: Defilers

Necroscope: Defilers Beneath the Moors and Darker Places

Beneath the Moors and Darker Places The Fly-By-Nights

The Fly-By-Nights Khai of Khem

Khai of Khem Ship of Dreams

Ship of Dreams The Nonesuch and Others

The Nonesuch and Others Blood Brothers

Blood Brothers Necroscope

Necroscope The Burrowers Beneath

The Burrowers Beneath Bloodwars

Bloodwars No Sharks in the Med and Other Stories

No Sharks in the Med and Other Stories The House of Doors - 01

The House of Doors - 01 Screaming Science Fiction

Screaming Science Fiction Necroscope III: The Source

Necroscope III: The Source Vampire World I: Blood Brothers

Vampire World I: Blood Brothers Iced on Aran

Iced on Aran Necroscope: Invaders

Necroscope: Invaders Necroscope: The Lost Years

Necroscope: The Lost Years Return of the Deep Ones: And Other Mythos Tales

Return of the Deep Ones: And Other Mythos Tales Necroscope V: Deadspawn

Necroscope V: Deadspawn Titus Crow, Volume 3: In the Moons of Borea, Elysia

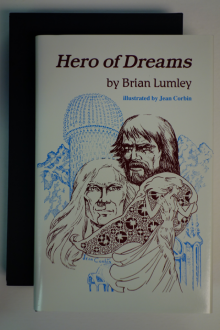

Titus Crow, Volume 3: In the Moons of Borea, Elysia Hero of Dreams

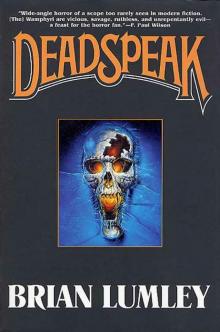

Hero of Dreams Necroscope IV: Deadspeak

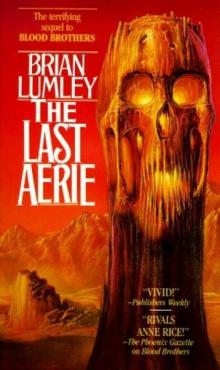

Necroscope IV: Deadspeak The Last Aerie

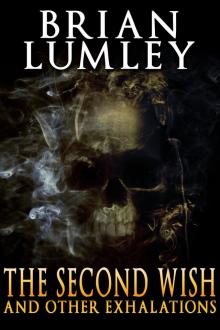

The Last Aerie The Second Wish and Other Exhalations

The Second Wish and Other Exhalations Necroscope: The Touch

Necroscope: The Touch Necroscope: The Plague-Bearer

Necroscope: The Plague-Bearer Necroscope: Avengers

Necroscope: Avengers Necroscope II: Wamphyri

Necroscope II: Wamphyri Necroscope II_Vamphyri!

Necroscope II_Vamphyri! A Coven of Vampires

A Coven of Vampires Spawn of the Winds

Spawn of the Winds Sorcery in Shad

Sorcery in Shad Deadspawn

Deadspawn Necroscope V: Deadspawn n-5

Necroscope V: Deadspawn n-5 Necroscope: Invaders e-1

Necroscope: Invaders e-1![Beneath the Moors and Darker Places [SSC] Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/beneath_the_moors_and_darker_places_ssc_preview.jpg) Beneath the Moors and Darker Places [SSC]

Beneath the Moors and Darker Places [SSC] Demogorgon

Demogorgon Harry and the Pirates_and Other Tales from the Lost Years

Harry and the Pirates_and Other Tales from the Lost Years Necroscope IV: Deadspeak n-4

Necroscope IV: Deadspeak n-4 Deadspeak

Deadspeak The Taint and Other Novellas

The Taint and Other Novellas Blood Brothers vw-1

Blood Brothers vw-1 The Source n-3

The Source n-3 In the Moons of Borea

In the Moons of Borea Avengers

Avengers Necroscope n-1

Necroscope n-1 Vamphyri!

Vamphyri! Questers for Kuranes: Two Tales of Hero and Eldin

Questers for Kuranes: Two Tales of Hero and Eldin Necroscope II: Wamphyri! n-2

Necroscope II: Wamphyri! n-2 The Source

The Source Elysia

Elysia The Plague-Bearer

The Plague-Bearer The Touch

The Touch Invaders

Invaders Necroscope 4: Deadspeak

Necroscope 4: Deadspeak Compleat Crow

Compleat Crow The Mobius Murders

The Mobius Murders Defilers

Defilers