- Home

- Brian Lumley

Necroscope: Defilers Page 16

Necroscope: Defilers Read online

Page 16

Fat for cooking? No problem. The restaurants in the inner city poured away thousands of gallons every night. They weren’t supposed to, but they did. A flusher’s nightmare, that: scraping or shovelling tons of that slop off of the walls and out of the pipes, before it hardened into giant candles and blocked up the entire works. Huh! And they wondered why the rat population was swelling the way it was!

Wally knew where there was a regular chimney of the stuff. The rats could chew all they wanted on the rancid external layers, but deep inside it was still pretty clean. It was similar to cheese, Wally thought: it went hard or stale on the outside but stayed soft in its core. He had a long-handled sugar scoop that could gouge right into it. And it smelled quite wonderful, of just about everything they’d been cooking up there. Sausages and beans could take on all kinds of oriental flavours …

As for toilets: three minutes in just about any direction, or less than that if you weren’t fussy. And Wally wasn’t especially fussy. Temperature? Winter or summer up above, down here it was constant, always mild; two blankets sufficed.

So he was home safe and dry, and all that remained was to visit the harem, let his ladies know he was back, and complain to them about the miserable day he’d had “upstairs.”

His ladies: an entire gallery of them on the walls of the tunnel adjoining his bedroom. He would have them in the bedroom itself, but that might prove too much of a distraction. There’s a time for sleeping and a time for the other—hence the harem. And now it was time for the other.

Wally had been looking forward to this moment all morning, and now his excitement grew as he sat down at his table (an old folding card table) and took out his magazines. Way back in the past there had been a men’s magazine called Playboy—the women had been beautiful, and the pictures soft-edged, warm and glowing, even “artistic” in a prurient sort of way. All of that was old hat these days, when art had given way to pure pornography. But the centrefold tradition still held true, if not to its origins.

Wally still kept a few of those old Playboy centrefolds pasted to the walls of his harem, but they were there for when the mood called for love, not lust. They were pictures of women he would have been able to love (if he’d been able and acceptable), not sluts with their legs gaping and their fingers holding themselves open for viewing! But the sad fact was that the majority of the glossily, lewdly pictured “ladies” in Wally’s harem were of the latter variety. For love had passed him by without a second glance, and lust was all that was left.

Removing the staples from the magazines, Wally spread the centrefolds on his table and examined them in torch-and candlelight. Flecks of drool dampened the corners of his mouth as he stared at close range at what would in most women be their most private places. But in these pictures he could look at and into them. He could look at them, touch them with trembling fingers and a fevered imagination, but never get into them or even near them “in the flesh.” But there was always the next best thing—which of necessity had ever been the way of it with Wally.

“A man’s best friend,” he told himself—hurrying with his paste pot, brush, his new lady-friends, and the throbbing penis with which they’d suddenly, spontaneously endowed him, through into his gallery, his harem—“is his good right wanking hand!” And with his torch jammed firmly in a gap where the mortar had fallen from between bricks in a gradually buckling wall, Wally quickly pasted up his new acquisitions.

Then, taking up his torch in his left hand, he began plying his fat, veined cock, aiming his torch first at one photograph, then the next, and slowly rotating to take in the entire gallery. This was what his ladies liked, he knew: that he shared his affections equally between them, showing no favoritism. But after he had turned full circle, returning to his “raw” recruits, then he made fast his torch in the wall again, so that it would hold steady as finally he brought himself to climax. Except that didn’t happen. For suddenly …

… There in the corner of Wally’s eye, a shadow where no shadow should be. And while his torch held steady in its crack in the wall, still the shadow moved, flowed—and it was cast by something behind Wally, something that was gradually occluding the torch’s beam.

And while he stood there frozen, still clutching his rapidly shrinking penis, so that grotesque shape—or shadow, or dark stain—flowed over the circle of light and plunged Wally’s ladies, and Wally himself, into inky darkness. And behind him something awesome breathed, just inches from his straining ears!

On legs like rubber, Wally turned, looked, saw …

Limned in weak torchlight, a jet-black silhouette, a fantastic shape, stood close. Scarlet eyes blinked, observing him closely and at close range. Then a hand—or something resembling a hand—reached out to settle on Wally’s shoulder. And as he gave a massive start:

“Ah, no!” said a low, dark voice like the gurgle of one of Wally’s drains. “Have no fear, my son, not of me. For we are as one. I have watched you for long and long: how you degrade yourself, hiding in the dark places like a moth, a fly-the-light—even like a Starside trog, or indeed like myself—because you are ugly. But believe me, you are by no means the ugliest.”

And the shape flowed to one side a little, until the edge of the beam of light fell more surely upon it. And turning its face right profile halfway into the light, it tilted its head inquiringly, opened wide its furnace eyes, and cracked its unbelievable jaws in such a smile that Wally—

—That Wally simply fainted dead away …

PART TWO

INTIMATIONS

7

PUTTING IT TOGETHER

Ben Trask slept late. After washing, shaving, and dressing, he made a few quick notes and was leaving his room to go to breakfast in the hotel downstairs (coffee, two slices of toast, and a boiled egg, as usual) when his phone rang. It was the Minister Responsible; he’d come through the duty officer and was on scrambled.

“Mr. Trask,” he began, “I’ve spoken to the director of the Bürger Finanz Gruppe bank and managed to extract you from your little pile of mess—again!”

“This early?” Trask glanced at his watch—not quite 9:30 A.M. in London—but of course Switzerland had started off the day an hour earlier.

“The early bird catches the worm, Mr. Trask. But really, I have to ask you to take a firmer hand with your people. I mean, I know the importance of what you’re doing, but—”

“But … I don’t think you do know,” Trask cut in. “If you did you’d have better things to do than come fishing for apologies, especially when I haven’t had breakfast yet. And when it comes to digging people out of the shit, how deep in it do you think you and the rest of the world would be if not for my people? Okay, so I had an ‘eager beaver’ who got ahead of herself. But it’s also possible she’s given us our best lead so far. So I’ve reprimanded her on the one hand, congratulated her on the other. Now then, do you approve? If you do, try unloading that chip off your shoulder. If you don’t, I’m open to suggestions. You could always retire me, I suppose.”

And after a brief silence: “Must you always take things so personally?” the Minister’s voice was still very calm, but much colder now. “I mean, where your people are concerned, Mr. Trask? Last night you were almost apologetic.”

“Last night I was very tired,” said Trask. “I’m talking about three years’ worth of tired—which to you probably indicates three years of not much happening, three years of running around and much ado about nothing? Maybe you’ve got used to the notion that these creatures are here, and since they don’t seem to be doing too much their threat no longer seems as great. But just because it was quiet for a while doesn’t mean it’s over—Australia proved that much. And yes, I do take things very personally where my people are concerned. It’s something they call loyalty. You should try it some time. Who knows, it might even be infectious.”

“Mr. Trask, now you’re trying to insult me!”

“I see it the other way round,” said Trask. “Were you out there in Australi

a with me, fighting these bloody vampire invaders of our world? Did you see people dying out there, blown to bits in booby traps? Was it you who—er, how did you put it?—’extracted me from that little pile of mess’ when it appeared I was next on the death list? Hell, no, it wasn’t you, it was my people. But you … you haven’t even found the time to say that you’re glad to see us all back in one piece. And now you expect me to grovel because you’ve ‘extracted me from a little pile of mess’? Of course I take it personally!”

Another brief silence, and then: “It’s true that I haven’t yet congratulated you on the Australian job,” the Minister said. “Well now I do so. I’m only asking you to remember that just as you answer to me—or rather, as you are supposed to answer to me—so I must answer to others above me. But sometimes answers are hard to come by. As you know, I coordinate our security services, Mr. Trask, which means that I’m just as covert in my work as you are in yours. And as vulnerable. When breaches of international etiquette occur, and when my people are responsible—for you are my people—then I’m liable to get just as upset as you. Our jobs are equally onerous, I assure you.”

Upset, Trask thought. Merely upset! The phlegmatism of the upper class English gentleman! But he had to smile, for he knew that what the Minister had said was very true. “Big fleas have little fleas upon their backs to bite ’em,” he quoted, and was rewarded by the other’s wry chuckle.

“I know the next line to that one,” the Minister answered. “‘And little fleas have smaller fleas, and so ad infinitum.’”

“And it also works in reverse, right?” Trask nodded. “We little fleas have to be careful how we ride the bigger ones in case they take umbrage and scratch us off. Okay, so thanks for helping us out …” And after a moment: “Can I take it that the director of the Burger Finanz Gruppe won’t be informing a certain ‘charity’ about a certain breach of security—or ‘etiquette,’ if you insist?”

“You can indeed,” the Minister said. “Also, if any further funding is to be released through that outlet, I’m assured that we’ll be advised well in advance.”

Trask jumped at that, making no attempt to hide his eagerness. “But will that help us? I mean, do we know where the outlet is? What town, city, country? I’d just love to be there if or when any more money is paid out. We could trace it right to our … well, let’s for the moment call him ‘our man.’ Or better still, our target. One of our targets.”

“No,” the Minister answered. “All of the Swiss banks still play it very close to their chests—er, their treasure chests? It’s the closest thing you’ll ever get to a doctor/patient relationship. Complete confidentiality. But anyway, good luck with whatever it is you’ve tracked down.”

“Tracking,” Trask corrected him. “We’re not there yet. And talking about not being there, my breakfast is waiting and I’ve a think tank in just an hour’s time. Thanks for calling, if not for the slap on the wrist.”

“Think nothing of it,” said the other. “But do please keep those eager beavers of yours on a leash, won’t you?” And before Trask could answer he put his phone down. As the Minister Responsible, he liked to have the last word.

Oh, I won’t, Trask told himself, meaning he wouldn’t think anything of it. Then, slightly ruffled on the one hand, pleased on the other, he left his E-Branch accommodation and went for a late breakfast …

Going into the think tank in a smaller room off Ops, Trask stopped Millicent Cleary and had a word with her in private. “I had to take a little flak from the man upstairs,” he told her. “But at least he took the heat off us. I’ll tell you about it later. Meanwhile, have you given any more thought as to where Malinari might be?”

Jimmy Harvey was squeezing by them where they stood inside the door. “I couldn’t help but hear that,” he said, keeping his voice down as he joined them.

“What part of it?” Trask looked him up and down. “And what in hell have you been doing to yourself? A rough night or something?”

Harvey cut a gnomish sort of figure. A short, compact man at five feet and four inches, he was the whiz-kid computer and communications expert who—along with Millie—had almost got Trask into trouble last night. In his midtwenties, and prematurely bald, but with long red sideburns and bushy eyebrows that tried hard to make up for his baldness; grey, watery eyes; and a positive genius for electronics, he did in fact remind Trask of a clever, occasionally mischievous gnome. Right now, though, there were bags under his eyes, his face was lined and sagging, and his clothes looked like he’d slept in them.

Yawning behind his hand, Harvey answered Trask’s question: “Last night, after Millie went off to talk to you, I sat around awhile in Ops—more than a while, actually. I didn’t hit the sack until around three A.M. But I found stuff to do … I was just following orders, putting in some of the extra time you’ve been asking for. Anyway, before I called it a night I fed some stuff into the extraps. This morning I was back in Ops, and the machines have come up with some interesting ideas.”

As Harvey finished speaking, Trask looked beyond him into the room. The other think-tank members were all assembled; they sat at a large, oblong table with notepads and pencils to hand. They were Ian Goodly, David Chung, Paul Garvey, and John Grieve, all of them longtime members of E-Branch; the “upper echelon,” as it were. The only one who was missing—who really should have been here—was Anna Marie English, but she was in Sunside. And Zek, of course, or Mrs. Trask, as they had all-too-briefly known her. But Zek wasn’t anywhere anymore, or if she was, then it was a place way beyond anyone’s ability to reach.

Beyond Trask’s abilities, anyway …

Others, who weren’t from the original cast, were Liz Merrick (who was here because of her connection with Jake Cutter), and Lardis Lidesci, chiefly because he was wont to jump in now and then with some pretty sharp, intuitive comments. Jimmy Harvey was a recent recruit; he was here to represent the techs.

“Let’s join them,” Trask said. “And we’ll start with you, Jimmy.” And then, as they seated themselves, Trask at the head of the table: “Good morning,” he greeted the others, then went straight into it. “We’re going to start off with Jimmy. He and Millie have been working, er, privately, on something with terrific potential. It would seem they’ve come up with the goods. We’re not there yet, but we’re certainly halfway. That’s what we’re here for—to finish what they’ve started. Thinking caps on, everyone, and let’s hear what Jimmy has to say. Jimmy?”

The tired-looking Harvey took it from there. “Millie and I did a little, er, poaching last night—that’s illicit fishing. Mr. Trask might want to enlarge on that later,” he glanced apprehensively at Trask, then at Millie, and quickly went on, “—or maybe not. Anyway, we narrowed down Malinari’s possible whereabouts to just a handful of countries, and later I fed them into one of the extraps together with some stuff we’d come across in Australia. By then it was late and I didn’t wait around to find out what the computer would come up with. But this morning—”

“Wait!” said Trask. “We’ll all be better off if we can see the whole picture. Just what was this stuff from Australia that you fed into the extrap?”

Harvey shrugged. “Well, for one there was the Bruce Trennier connection. He was an Aussie, or a New Zealander, which to me seemed close enough. And then there’s the fact that the Australian tropics are just about as far as possible from where we would normally have expected to find Malinari. And, since I was putting Trennier’s name in there, it seemed sensible to include the names of the others who were taken from the Refuge when the Wamphyri came through. So I also entered details from our files on Andre Corner and Denise Karalambos. And finally, I requested the odds on our short list of locations.”

“Corner and Karalambos,” Trask frowned, and Millie Cleary stepped in:

“Andre Corner was a Harley Street psychiatrist who specialized in kids and young adults,” she said. “He’d long since made his pile and wanted to give something back. His teenage son had

died of a massive drugs overdose. Corner’s self-imposed penance—for letting his son down, I suppose—was to work at the Refuge as a volunteer, helping all those young Romanian people.”

Trask nodded. “Yes, I remember now …” It should have been hard to forget, really, but he’d erased a lot of the details of that time from his mind. “And Denise Karalambos was—?”

“She was a paediatrician from Athens, another volunteer,” Millie obliged.

Things were coming together now, and Trask—and probably everyone else—was beginning to see where this was going.

“How come these things—these names and details—weren’t already in the computer?” Trask wanted to know.

“They were,” Harvey answered. “But the extraps aren’t programmed to play hunches. They only work with hard facts, and we hadn’t been asking the right questions.”

And David Chung, the locator, came in with: “That’s right. Instead of describing Starside as their sort of habitation, and trying to predict where the Wamphyri would feel most at home in our world, we’d have been a lot better off trying to figure out where their new lieutenants were likely to take them!”

“So,” Ian Goodly piped up. “Just exactly what did your extrap come up with, Jimmy?”

Mad Moon of Dreams

Mad Moon of Dreams Psychosphere

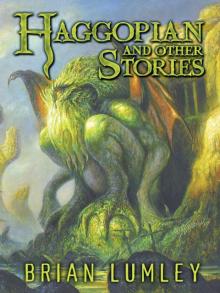

Psychosphere Haggopian and Other Stories

Haggopian and Other Stories Resurgence_The Lost Years_Volume Two

Resurgence_The Lost Years_Volume Two Necroscope: Harry and the Pirates: And Other Tales From the Lost Years

Necroscope: Harry and the Pirates: And Other Tales From the Lost Years Necroscope®

Necroscope® Dreamlands 5: Questers for Kuranes: Two Tales of Hero and Eldin

Dreamlands 5: Questers for Kuranes: Two Tales of Hero and Eldin The Taint and Other Novellas: Best Mythos Tales Volume 1

The Taint and Other Novellas: Best Mythos Tales Volume 1 Necroscope: Defilers

Necroscope: Defilers Beneath the Moors and Darker Places

Beneath the Moors and Darker Places The Fly-By-Nights

The Fly-By-Nights Khai of Khem

Khai of Khem Ship of Dreams

Ship of Dreams The Nonesuch and Others

The Nonesuch and Others Blood Brothers

Blood Brothers Necroscope

Necroscope The Burrowers Beneath

The Burrowers Beneath Bloodwars

Bloodwars No Sharks in the Med and Other Stories

No Sharks in the Med and Other Stories The House of Doors - 01

The House of Doors - 01 Screaming Science Fiction

Screaming Science Fiction Necroscope III: The Source

Necroscope III: The Source Vampire World I: Blood Brothers

Vampire World I: Blood Brothers Iced on Aran

Iced on Aran Necroscope: Invaders

Necroscope: Invaders Necroscope: The Lost Years

Necroscope: The Lost Years Return of the Deep Ones: And Other Mythos Tales

Return of the Deep Ones: And Other Mythos Tales Necroscope V: Deadspawn

Necroscope V: Deadspawn Titus Crow, Volume 3: In the Moons of Borea, Elysia

Titus Crow, Volume 3: In the Moons of Borea, Elysia Hero of Dreams

Hero of Dreams Necroscope IV: Deadspeak

Necroscope IV: Deadspeak The Last Aerie

The Last Aerie The Second Wish and Other Exhalations

The Second Wish and Other Exhalations Necroscope: The Touch

Necroscope: The Touch Necroscope: The Plague-Bearer

Necroscope: The Plague-Bearer Necroscope: Avengers

Necroscope: Avengers Necroscope II: Wamphyri

Necroscope II: Wamphyri Necroscope II_Vamphyri!

Necroscope II_Vamphyri! A Coven of Vampires

A Coven of Vampires Spawn of the Winds

Spawn of the Winds Sorcery in Shad

Sorcery in Shad Deadspawn

Deadspawn Necroscope V: Deadspawn n-5

Necroscope V: Deadspawn n-5 Necroscope: Invaders e-1

Necroscope: Invaders e-1![Beneath the Moors and Darker Places [SSC] Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/beneath_the_moors_and_darker_places_ssc_preview.jpg) Beneath the Moors and Darker Places [SSC]

Beneath the Moors and Darker Places [SSC] Demogorgon

Demogorgon Harry and the Pirates_and Other Tales from the Lost Years

Harry and the Pirates_and Other Tales from the Lost Years Necroscope IV: Deadspeak n-4

Necroscope IV: Deadspeak n-4 Deadspeak

Deadspeak The Taint and Other Novellas

The Taint and Other Novellas Blood Brothers vw-1

Blood Brothers vw-1 The Source n-3

The Source n-3 In the Moons of Borea

In the Moons of Borea Avengers

Avengers Necroscope n-1

Necroscope n-1 Vamphyri!

Vamphyri! Questers for Kuranes: Two Tales of Hero and Eldin

Questers for Kuranes: Two Tales of Hero and Eldin Necroscope II: Wamphyri! n-2

Necroscope II: Wamphyri! n-2 The Source

The Source Elysia

Elysia The Plague-Bearer

The Plague-Bearer The Touch

The Touch Invaders

Invaders Necroscope 4: Deadspeak

Necroscope 4: Deadspeak Compleat Crow

Compleat Crow The Mobius Murders

The Mobius Murders Defilers

Defilers