- Home

- Brian Lumley

Deadspeak Page 15

Deadspeak Read online

Page 15

Harry opened his eyes and caught Bettley staring at him. He said nothing, merely stared back. That’s what he was here for: to be stared at, to be examined. And Bettley was good at his job, and discreet. Everybody said so. He had many admirable qualities. Must have, else E-Branch would never have taken him on. And again Harry wondered, Is he still working for them? Not that it would matter a great deal, for Bettley was easy to talk to. It was just that Harry so hated subterfuge.

The doctor continued to stare into Harry’s eyes. They were soulful as ever, and somehow defensive; but at the same time it seemed that Harry needed this close contact. Honey brown, those eyes; very wide, very intelligent, and (strange beyond words) very innocent! Genuinely innocent, Bettley knew. Harry Keogh had not asked to be what he was, or to be called upon to do the things he’d done.

Bettley forced himself back to the job in hand. “So I’m half-wrong,” he said. “You would like your talents back, to be a ‘freak’ again—your words, Harry. But what will you do with those talents if they do return to you? How will you use them?”

Harry gave a wry smile. His teeth were good and strong, not quite white, a little uneven; they were set in a mouth which was usually sensitive but could tighten, becoming caustic and even cruel. Or perhaps not so much cruel as unyielding, single-minded.

“You know, I scarcely knew my mother,” he dreamily answered. “I was too young, just a baby, when she died. But I got to know her … later. And I miss her. A boy’s best friend is his mum, you know? And … well, I have a lot of friends down there.”

“In the ground?”

“Yes. Hell, we had some good conversations!”

Bettley almost shuddered, fought it down. “You miss talking to them?”

“They had their problems, wanted to air their views, wondered how things had gone in the world of the living. Some of them worried a lot, about people they’d left behind. I was able to reassure them. But most were merely lonely. Merely! But I knew what it was like for them. I could feel it. It was hell to be that lonely. They needed me; I was somebody to them; and I suppose I miss them needing me.”

“But none of this explains your dream,” the doctor mused. “Maybe it has no explanation—except fear. You’ve lost your friends, your skills, those parts of yourself that made you unique. And now you’re afraid of losing your manhood.”

Harry narrowed his eyes a little and began to pay more attention; he looked at Bettley more piercingly. “Explain.”

“But isn’t it obvious? A disembodied female thing—a dead thing, a vampire thing—devours your core, the parts of you that make you a man. She was fear, your fear, pure but not so simple. Her vampire nature was straight out of your own past experience. You don’t like being normal, and the more you have to endure it the more afraid of it you get to be. It’s all tied up to your past, Harry: it’s all the things you’ve lost until you’re afraid of losing anything else. You lost your mother when you were a child, lost your own wife and child in an unreachable place, lost so many friends and even your own body! And finally you’ve lost your talents. No more Möbius Continuum, no more talking to the dead, no more Necroscope …”

Harry was frowning now. “What you said about vampires made me remember something,” he said. “Several things, in fact.” He went back to rubbing his brow.

“Go on,” Bettley prompted him.

“I have to start some way back,” Harry continued, “when I was a kid at Harden Modern Boys. That’s a school. I was a Necroscope even then, but it wasn’t something I much liked. It used to make me dizzy, sick even. I mean it came naturally to me, but I knew it wasn’t. I knew it was very unnatural. But even before that I used to … well, see things.”

Bettley was an empath; now he felt something of what Harry felt and the short hairs began to rise at the back of his neck. This was going to be important. He glanced down at a button on his side of the desk: it was still red, the tape was still running. “What sort of things?” he asked, hiding his eagerness.

“I was an infant when my stepfather killed my mother,” the other answered. “I wasn’t on the scene, and even if I had been, I wasn’t old enough for it to impress me. I couldn’t possibly have understood what was happening, and almost certainly I wouldn’t have remembered it. And I couldn’t have reconstructed it later from overheard conversations because Shukshin’s account of the ‘accident’ had been accepted. There was no question of his having murdered her—except from me. It was a nightmare I used to have: of him holding her there under the ice, until she drifted away. And I saw the ring on his finger: a cat’s-eye set in a thick gold band. It came off when he drowned her and sank to the bottom of the river, and fifteen years later I knew where to go back and dive for it.”

Bettley felt a tingling in his spine. “But you were a Necroscope —the Necroscope—and read it out of your dead mother’s mind. Surely?”

Harry shook his head. “No, because it was a dream I had from a time long before I first consciously talked to the dead. And in it I ‘remembered’ something I couldn’t possibly remember. It was a talent I’d had without even recognising it! You know my mother was a psychic medium, and her mother too? Maybe it was something that came down from them. But as my greater talent—as a Necroscope—developed, so this other thing was pushed into the background, got lost.”

“And you think all of this has something to do with this new dream of yours? In what way?”

Harry’s shrug was lighter, no longer defeatist. “You know how when someone goes blind he seems to develop a sixth sense? And people handicapped from birth, how they seem to make up for their deficiencies in other ways?”

“Of course,” the doctor answered. “Some of the greatest musicians the world’s ever seen have been deaf or blind. But what … ?” And then he snapped his fingers. “I see! So you think that the loss of your other talents has caused this … this atrophied one to start growing again, is that it?”

“Maybe”—Harry nodded—“maybe. Except I’m not just seeing things from the past anymore but from the future. My future. But vaguely, unformed except as nightmares.”

It was Bettley’s turn to frown. “A precog, is that what you think you’re becoming? But what has this to do with vampires, Harry?”

“It was my dream,” the other answered. “Something I’d forgotten, or hadn’t wanted to remember, until you brought it back to me. But now I remember it clearly. I can see it clearly.”

“Go on.”

“It’s just a little thing.” Harry shrugged again, perhaps defensively.

“But best if we have it out in the open, right?” Bettley spoke quietly, clearing the way for Harry without openly urging him on.

“Perhaps.” And in a sudden rush of words: “I saw red threads! The scarlet life threads of vampires!”

“In your dream?” Bettley shivered as gooseflesh crept on his back and forearms. “Where in your dream?”

“In the green stripes where the light came through the blinds,” Harry answered. “The stripes on her belly and thighs, in the moment before that hellish thing fastened on me. They were green-tinted, almost submarine, but as my blood began to spurt they turned red. Red stripes streaming off her body into the dim past, and also into the future. Writhing red threads among the blue life threads of humanity. Vampires!”

The doctor said nothing, waited, felt the other’s horror—and fascination—washing out from him, welling into the study like a sick, almost tangible flood tide. Until Harry shook his head and cut it off. Then, abruptly, he stood up and headed a little unsteadily for the door.

“Harry?” Bettley called after him.

At the door Harry turned. “I’m wasting your time,” he said. “As usual. Let’s face it, you could be right and I’m frightened of my own shadow. Self-pity, because I’m nothing special anymore. And maybe scared because I know what could be out there waiting for me, but probably isn’t. But what the hell—what will be will be, we know that. And the time is long past when I could do anyth

ing about it or change any part of it.”

Bettley shook his head in denial. “It wasn’t a waste, Harry, not if we got something out of it. And it seems to me we got a lot out of it.”

The other nodded. “Thanks anyway,” he said, and closed the door behind him. The doctor got up and moved to his window. Shortly, down below, Harry left the building and stepped out into Princes Street in the heart of Edinburgh. He turned up his coat collar against the squalling rain, tucked his chin in, and angled his back to the bluster, then stepped to the kerb and hailed a taxi. A moment later and the car had whirled him away.

Bettley returned to his desk, sat down, and sighed. Now he was the one who felt weak; but Keogh’s psychic essence—a near-tangible “echo” of his presence—was already fading. When it had faded into nothing, the empath rewound his interview tape and dialled a special number at E-Branch HQ in London. He waited until he got a signal, then placed the handset into a cradle on the tape machine under his desk. At the press of a button, Harry’s interview began playing itself into storage at E-Branch.

Along with all of his other interviews …

In the back of the taxi on the way to Bonnyrig, Harry relaxed and closed his eyes, leaned his head against the seat, and tried to recall something of that other dream which had bothered him on and off for the last three or four years, the one about Harry Jr. He knew what the dream was in essence—what had been done to him, how, and why—but its fine detail eluded him. The what and how part was obvious: by use of the Wamphyri art of fascination, hypnotism, Harry Jr. had made his father an ex-Necroscope, at the same time removing or cancelling his ability to enter and manoeuvre in the Möbius Continuum. As to why he’d done it:

You would destroy me if you could, he heard his son’s voice again, like a record played a hundred times, until he knew every word and phrase, every mood and emotion or lack of it, by heart. Don’t deny it, for I can see it in your eyes, smell it on your breath, read it in your mind. I know your mind well, Father. Almost as well as you do. I’ve explored every part of it, remember?

And now, under his breath, Harry answered again as he’d answered then, “But if you know that much, then you know I’d never harm you. I don’t want to destroy you, only to cure you.”

As you “cured” the Lady Karen? And where is she now, Father? It hadn’t been an accusation; there’d been no sarcasm in it, no sourness; it was just a statement of fact. For the Lady Karen had killed herself, which Harry Jr. knew well enough.

“The thing had taken too strong a hold on her,” Harry had insisted. “Also, she’d been a peasant, a Traveller, without your understanding. She couldn’t see what she’d gained, only what she thought she’d lost. She didn’t have to kill herself. Maybe she was … unbalanced?”

You know she wasn’t. She was simply Wamphyri. And you drove her vampire out and killed it. You thought it would be like killing a tapeworm, like lancing a boil or cutting out a cancer. But it wasn’t. You say she couldn’t see what she d gained. Now tell me, Father, what you think the Lady Karen had gained?

“Her freedom!” Harry had cried in desperation, and in sudden horror of himself. “For God’s sake, don’t prove me wrong in what I did! I’m no bloody murderer!”

No, you’re not. But you are a man with an obsession. And I’m afraid of you. Or if not afraid of you, afraid of your goals, your ambitions. You want a world—your world—free of vampirism. An entirely admirable objective. But when you’ve achieved that aim … what then? Will my world be next? An obsession, yes, which seems to be growing in you even as my vampire is growing in me. I’m Wamphyri now, Father, and there’s nothing so tenacious as a vampire—unless it’s Harry Keogh himself!

Can’t you see how dangerous you are to me? You know many of the secret arts of the Wamphyri, and how to destroy them; you can talk to the dead, travel in the Möbius Continuum—even in time itself, however ephemerally. I ran away from you, from your world, once. But now, in this world, I’ve fought for my territories and earned them. They’re mine now and I’ll not desert them. I’ll run no more. But I can’t take the chance that you won’t come after me, daren’t accept the risk that you won’t be satisfied. I’m Wamphyri! I’ll not suffer your experiments. I’ll not be a guinea pig for any more “cures” you might come up with.

“And what of me?” Harry had spoken up then, even as he now whispered the words to himself. “How safe will I be? I’m a threat to you, you’ve admitted as much. How long before your vampire is ascendant and you come looking for me?”

But that won’t happen, Father. I’m not a peasant; I do have knowledge; I shall control myself as a clever addict controls his addiction.

“And if it gets out of control? You, too, are a Necroscope. And in the Möbius Continuum there’s nothing you can’t do, nowhere you can’t go, and always carrying your contamination with you. What poor bastard will get your egg, son?”

At which Harry Jr. had sighed heavily and taken off his golden mask. His scars from the battle in the Garden had healed now; there was nothing much to be seen of them; his vampire had been busy repairing him, moulding his flesh as his father feared it would one day mould his will. So you see we’re at stalemate, he’d said. And his eyes had opened into huge crimson orbs.

“No!” Harry gasped out loud, now as he’d gasped it then. Except that then it had been the last thing he’d said for quite some time, until he’d woken up at E-Branch. Whereas now:

“Whazzat, Chief?” his dour-faced driver glanced back at him, frowning and puzzled. “But did ye no say Bonnyrig? Ah surely hope so, ‘cos we’re a’most there!”

The real world crashed down on Harry. He was sitting upright, stiff and pale, with his bottom jaw hanging slightly open. He licked his dry lips and looked out through the taxi’s windows. Yes, they were almost there. And:

“Bonnyrig, yes, of course,” he mumbled. “I was … I was daydreaming, that’s all.” And he directed the other through the village and to his house …

North London in late April 1989; a fairly rundown bottom-floor flat in the otherwise “upwardly mobile” district of Highgate just off Hornsey Lane; two men, apparently relaxed, talking quietly over drinks in a large sitting room lined with bookshelves full of books and many small items of foreign, mainly European bric-a-brac …

Very untypical of his race, Nikolai Zharov was slender as a wand, pale as milk, almost effeminate in his affectations. He used a cigarette holder to smoke Marlboros with their filters torn off, spoke excellent English albeit with a slight lisp, and had in general a rather lirnp-wristed air. His eyes were dark, deep set and heavy-lidded, giving him an almost-drugged appearance which belied the alert and ever-calculating nature of his brain.

His hair was thin and black, swept back, lacquered down with some antiseptic-smelling Russian preparation; under a thin, straight nose his lips were also thin in a too-wide mouth. A pointed chin completed his lean look; he appeared the sort who might easily bend but never break; “real men” may be tempted to look at him askance but they wouldn’t push their luck with him. Out in the city’s streets Zharov would certainly warrant a second glance, following which the observer would very likely look away. The Russian would tend to make people feel uneasy.

He made Wellesley uneasy, for a fact, though the latter tried hard to conceal it. As owner of the flat, Wellesley was worried someone might have seen his visitor coming here, or even followed him. Which would be one hell of a difficult thing to explain away. For Wellesley was a player in the intelligence game, and so was Zharov, though ostensibly they worked for different bosses.

At five feet eight inches tall Norman Harold Wellesley was some five or six inches shorter than the spindly Russian; he had more meat on him, too, and more colour in his face. Too much colour. But it wasn’t his stature or mildly choleric mottling that put him at a disadvantage. His current mental agitation hailed not so much from physical or even cultural disparities of race and type as from fear pure and simple. Fear of what Zharov was asking him to do.

/>

In answer to which he had just this moment replied, “But you must know that’s plainly out of the question, not feasible, indeed little short of impossible!” Explosive-seeming words, yet uttered quietly, coldly, even with a measure of calculation. A calculated attempt to dissuade Zharov from his course, or perhaps reroute it a little, even knowing that he wasn’t the author of the “request” he’d made but merely the delivery boy.

And the Russian had obviously expected as much. “Wrong,” he answered, just as quietly, but with something of a cold smile to counter the other’s flush. “Not only is it entirely possible but imperative. If, as you have reported, Harry Keogh is on the verge of developing new and hitherto unsuspected talents, then he must be stopped. It is as simple as that. He has been a veritable plague on Soviet ESPionage, Norman. A disaster, a mental hurricane … a psiclone? Oh, our E-Branch survives, lives on despite all his efforts, but barely.” Zharov shrugged. “On the other hand, perhaps we should be grateful to him: his, er, successes have made us more than ever aware of the power of parapsychology—its importance—in the field of spying. The problem is that as a weapon he gives your side far too much of an edge. Which is why he has to go …”

If Wellesley had been paying any real attention to Zharov’s argument, it hardly showed. “You will recall—” he now started to reply. “I mean, you have probably been informed—that my initial liability was a small one? Very well, I owe your masters a small favour—I’m in their debt, let’s say—but not such a large debt even now. And their interest rates are way too high, my friend. Beyond my limited ability to pay. I’m afraid that’s my answer, Nikolai, which you must take back with you to Moscow.”

Zharov sighed, put down his drink, and leaned back in his chair. He stretched his long legs, folded his arms across his chest, and pursed his lips; he allowed his heavy eyelids to droop more yet. The pupils of his dark eyes glinted from their cores, and for several long moments he studied Wellesley where he was seated on the opposite side of a small occasional table.

Mad Moon of Dreams

Mad Moon of Dreams Psychosphere

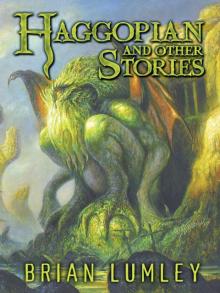

Psychosphere Haggopian and Other Stories

Haggopian and Other Stories Resurgence_The Lost Years_Volume Two

Resurgence_The Lost Years_Volume Two Necroscope: Harry and the Pirates: And Other Tales From the Lost Years

Necroscope: Harry and the Pirates: And Other Tales From the Lost Years Necroscope®

Necroscope® Dreamlands 5: Questers for Kuranes: Two Tales of Hero and Eldin

Dreamlands 5: Questers for Kuranes: Two Tales of Hero and Eldin The Taint and Other Novellas: Best Mythos Tales Volume 1

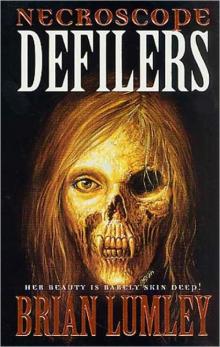

The Taint and Other Novellas: Best Mythos Tales Volume 1 Necroscope: Defilers

Necroscope: Defilers Beneath the Moors and Darker Places

Beneath the Moors and Darker Places The Fly-By-Nights

The Fly-By-Nights Khai of Khem

Khai of Khem Ship of Dreams

Ship of Dreams The Nonesuch and Others

The Nonesuch and Others Blood Brothers

Blood Brothers Necroscope

Necroscope The Burrowers Beneath

The Burrowers Beneath Bloodwars

Bloodwars No Sharks in the Med and Other Stories

No Sharks in the Med and Other Stories The House of Doors - 01

The House of Doors - 01 Screaming Science Fiction

Screaming Science Fiction Necroscope III: The Source

Necroscope III: The Source Vampire World I: Blood Brothers

Vampire World I: Blood Brothers Iced on Aran

Iced on Aran Necroscope: Invaders

Necroscope: Invaders Necroscope: The Lost Years

Necroscope: The Lost Years Return of the Deep Ones: And Other Mythos Tales

Return of the Deep Ones: And Other Mythos Tales Necroscope V: Deadspawn

Necroscope V: Deadspawn Titus Crow, Volume 3: In the Moons of Borea, Elysia

Titus Crow, Volume 3: In the Moons of Borea, Elysia Hero of Dreams

Hero of Dreams Necroscope IV: Deadspeak

Necroscope IV: Deadspeak The Last Aerie

The Last Aerie The Second Wish and Other Exhalations

The Second Wish and Other Exhalations Necroscope: The Touch

Necroscope: The Touch Necroscope: The Plague-Bearer

Necroscope: The Plague-Bearer Necroscope: Avengers

Necroscope: Avengers Necroscope II: Wamphyri

Necroscope II: Wamphyri Necroscope II_Vamphyri!

Necroscope II_Vamphyri! A Coven of Vampires

A Coven of Vampires Spawn of the Winds

Spawn of the Winds Sorcery in Shad

Sorcery in Shad Deadspawn

Deadspawn Necroscope V: Deadspawn n-5

Necroscope V: Deadspawn n-5 Necroscope: Invaders e-1

Necroscope: Invaders e-1![Beneath the Moors and Darker Places [SSC] Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/beneath_the_moors_and_darker_places_ssc_preview.jpg) Beneath the Moors and Darker Places [SSC]

Beneath the Moors and Darker Places [SSC] Demogorgon

Demogorgon Harry and the Pirates_and Other Tales from the Lost Years

Harry and the Pirates_and Other Tales from the Lost Years Necroscope IV: Deadspeak n-4

Necroscope IV: Deadspeak n-4 Deadspeak

Deadspeak The Taint and Other Novellas

The Taint and Other Novellas Blood Brothers vw-1

Blood Brothers vw-1 The Source n-3

The Source n-3 In the Moons of Borea

In the Moons of Borea Avengers

Avengers Necroscope n-1

Necroscope n-1 Vamphyri!

Vamphyri! Questers for Kuranes: Two Tales of Hero and Eldin

Questers for Kuranes: Two Tales of Hero and Eldin Necroscope II: Wamphyri! n-2

Necroscope II: Wamphyri! n-2 The Source

The Source Elysia

Elysia The Plague-Bearer

The Plague-Bearer The Touch

The Touch Invaders

Invaders Necroscope 4: Deadspeak

Necroscope 4: Deadspeak Compleat Crow

Compleat Crow The Mobius Murders

The Mobius Murders Defilers

Defilers