- Home

- Brian Lumley

Necroscope® Page 12

Necroscope® Read online

Page 12

Keogh’s grandfather had been Irish, moving from Dublin to Scotland in 1918 at the end of the war and working in Glasgow as a builder. His grandmother had been a Russian lady of some note, who fled the Revolution in 1920 and took up residence in an Edinburgh house close to the sea. There Sean Keogh met her, and in 1926 they’d been married. Three years later Harry’s uncle Michael was born, and in 1931 his mother, Mary. Sean Keogh had been hard on his son, apparently, bringing him into the building business (which he’d hated) and working him hard from the age of fourteen; but by comparison he had seemed literally to dote on his daughter, for whom nothing had ever been good enough. This had caused some jealousy between brother and sister, which came to an end when Michael was nineteen and ran off south to set himself up in a business of his own. Michael was the uncle Harry Keogh now lived with.

By the time Mary Keogh was twenty-one, however, her father’s doting had turned to a fierce possessiveness which totally shut her off from any sort of social life, so that she stayed mainly at home and helped with the housework, or assisted her aristocratic Russian mother in the small psychic circle she had built up, where she would attend and regularly take part in those séances for which Natasha Keogh had become something of a local celebrity.

Then, in the summer of ’53, Sean Keogh had been killed when an unsafe wall he was working on fell on him. His wife, who for all that she was not yet fifty was already ailing, had sold the business and gone into semi-retirement, holding the occasional séance to eke out her living, which now mainly derived from the interest on banked money. For Mary, on the other hand, the death of her father had heralded a hitherto undreamed-of freedom; quite literally, a “coming out.”

For the next two years she enjoyed a social life limited only by her tiny allowance, until by the winter of ’55 she had met and married an Edinburgh man twenty-five years her senior, a banker in the city. He was Gerald Snaith, and he and Mary had been very happy for all the gap in their age groups, living in a large house in its own private grounds not far from Bonnyrigg. Unfortunately, by then Mary’s mother was rapidly sickening and her doctors had diagnosed cancer; so that Mary lived half of her time at Bonnyrigg, and the rest of it looking after her mother, Natasha, at the seaside house in Edinburgh.

Harry ‘Keogh’ was therefore born Harry Snaith just nine months after his grandmother died in 1957—and just a year before his banker father would follow her, dying from a stroke in his office at the bank.

Mary Keogh was a strong girl and still very young. She had already sold the old family house by the sea and now found herself sole beneficiary of her husband’s not inconsiderable estate. Deciding to get away from Edinburgh for a little while, in the spring of ’59 she had come down to Harden and hired a house until the end of July, spending a lot of time in becoming reconciled with her brother and in getting to know his new wife. During that time she saw how his business was declining and helped out with sufficient hard cash to tide him over.

It was then, too, that Michael first detected an aura of sadness or hopelessness about his sister. When he asked what was bothering her (other, of course, than the recent death of her husband, which still weighed heavily) she reminded him of their mother’s “sixth sense,” her psychic sensitivity. She believed she had inherited something of it; it “told” her that she would not have a long life. That didn’t worry her unduly—what would be would be—but she did worry about little Harry. What would become of him, if anything should happen to her while he was still a child?

It was unlikely that Michael Keogh and his wife, Jenny, would be able to have children of their own. They had known this when they married, but mutually agreed that it was not a matter of overriding importance; their feelings for each other came first. Later, when their small business was better established, there would be time enough to consider adoption. In these circumstances, however, and if anything should “happen” to Mary—a prediction which, while her brother himself put little store by it, Mary seemed strongly inclined, indeed resolved, towards—then she would not need to let it concern her. Of course her brother and his wife would bring up little Harry as their own. The “promise” was made more to put her mind at rest than as a real promise as such.

When Harry was two his mother met and was “swayed” by a man only two or three years older than herself, one Viktor Shukshin, an assumed dissident who had made his way to the West in pursuit of a political haven, or at least political freedom, such as Mary Keogh’s mother had done in 1920. Perhaps Mary’s fascination with Shukshin was due to this “Russian connection,” but whichever, she married him late in 1960 and they lived at the house near Bonnyrigg. A linguist, Harry’s new stepfather had been giving private lessons in Russian and German in Edinburgh for the last two years; but now, all financial problems set aside, he and his new wife gave themselves over to a life of leisure and personal interests and inclinations. He, too, was greatly interested in the “paranormal,” encouraging his wife in her psychic pursuits.

Michael Keogh had met Shukshin at his sister’s wedding, and again, briefly, while on a touring holiday in Scotland—but after that … only at the inquest. For in the winter of ’63 Mary Keogh died, as she had predicted, at only thirty-two years of age. Of Shukshin himself: Hannant had only ascertained that the Keoghs hadn’t liked the man. There had been that about him which alienated them; probably the same thing which had attracted Michael’s sister.

As to Mary’s death:

She had been a skater, had loved the ice. A river within view of the house near Bonnyrigg had claimed her, when she had apparently fallen through thin ice while skating and been swept away. Viktor had been with her but had been unable to do anything. Distraught—almost out of his mind with horror—he had gone for help, but.…

Beneath the ice, the river had been swollen, rushing, at the time of the accident. Downriver were many little backwaters where Mary’s body might have been washed up under the ice, remaining there until the thaw. Lots of mud had been washed down out of the hills, too, and this had doubtless covered her. At any rate, her body was never found.

Within six months Michael had fulfilled his promise; Harry “Keogh” had gone to live with his uncle and aunt in Harden. This had suited Shukshin; Harry had not been his child, and he was in any case middling with children and did not feel inclined to bring the boy up on his own. Mary’s will had made good provision for Harry; the house and the rest of her estate went to the Russian. To Michael Keogh’s knowledge, Shukshin lived there yet; he had not remarried but gone back to giving private tuition in German and Russian. He still gave lessons at the house near Bonnyrigg, where he apparently lived alone. Not once over the years had he asked to see Harry, nor even enquired about him.

Dramatic as his family history might seem, still, all in all, Harry Keogh’s beginnings had not been very remarkable. The only matter which had made any real impression on Hannant had been Keogh’s grandmother’s and mother’s predilection for the paranormal; but that in itself was not very extraordinary. Or there again … perhaps it was. Mary Shukshin had seemed convinced that Natasha’s “powers” had been passed down to her, and what if she in turn had passed them down to Harry? Now there was a thought! Or there might be one, if Hannant believed at all in such things.

But he did not.

* * *

It was an evening some three weeks later, four or five days after Keogh had left Harden Modern Boys’ for the Tech., when Hannant stumbled across one final “oddity” concerning the boy.

Up in Hannant’s attic he’d long kept an old trunk of his father’s containing one or two books and bundles of old papers, dusty bits of bric-à-brac and various mementoes of the old man’s years of teaching. Having gone up there to fix a tile loosened in a brief storm off the North Sea, he had seen the trunk and admired it. Stoutly constructed, its dark body and brass hasps and hinges retained an olde-worlde appeal. It would create a very handsome effect beside the bookshelves in Hannant’s front room.

Dragging the tr

unk downstairs, he had started to empty it, glancing again at old photographs unseen for many a year, and putting aside items which might be useful at school (several old textbooks, for example) until he’d come across a large leather-bound notebook full of notes and jottings in his father’s hand. Something about the pattern and layout of his father’s work had held his eye for a moment … until it dawned on him just exactly what it was—or what he thought it was.

In the next moment that awful inexplicable chill had come again to strike Hannant’s spine, causing him to tremble where he sat holding the book open in his lap, stiffening his back with shock. Then … he had snapped the book shut, carried it through to his front room where a coal fire blazed beneath the wide chimney-piece. There, without even glancing at the book again, he thrust it into the flames and let it burn.

That same day Hannant had collected Keogh’s old maths books from the school for forwarding on to Harmon at the Tech. Now, taking the most recent one, he let its pages fall open for one last glance, then closed it with a shudder and let it join his father’s old book in the flames.

Prior to Keogh’s—awakening?—his work had been scruffy, lacking in order, by no means precise. Afterwards, for the last six or seven weeks.…

Well, the books were gone now, roared up in a sheet of flame and lost in the chimney, lost to the night.

There was no comparing them now, and that was probably the best way. To consider that there might be any real comparison would be too gross, too grotesque. Now Hannant could put the whole thing out of his mind forever. Thoughts like that had never belonged in any completely sane mind in the first place.

CHAPTER FOUR

It was the summer of 1972 and Dragosani was back in Romania. He looked very trendy in a washed-out blue open-necked shirt, flared grey trousers cut in Western style, shiny black shoes with sharply pointed toes (unlike the customary square-cut imported Russian footwear in the local shops) and a fawn-chequered jacket with large patch pockets. In the hot Romanian midday, especially at this farm on the outskirts of a tiny village some way off the Corabia-Calinesti highway, he stood out like the proverbial sore thumb. Leaning on his car and scanning the huddled rooftops and snail-shell cupolas of the village, which stood a little way down the gently sloping fields to the south, he could only be one of three things: a rich tourist from the West, one from Turkey, or one from Greece.

But on the other hand his car was a Volga and black as his shoes, which suggested something else. Also, he didn’t wear the wide-eyed, wary/innocent look of the tourist but a self-satisfied air of familiarity, of belonging. Approaching him from the farmhouse yard where he’d been feeding chickens, Hzak Kinkovsi, the “proprietor,” couldn’t make up his mind. He was expecting tourists later in the week, but this one had got him beat. He sniffed suspiciously. An official, maybe, from the Ministry of Lands and Properties? Some snotty lackey for those stone-faced Bolshevik industrialists across the border? He’d have to watch his step here, obviously. At least until he knew who or what the newcomer was.

“Kinkovsi?” the young man inquired, eyeing him up and down. “Hzak Kinkovsi? They told me in Ionestasi that you have rooms. I take it that place—” (a nod towards a tottering three-storied stone-built house by the cobbled village road) “—is your guesthouse?”

Kinkovsi deliberately looked blank, feigned a lack of understanding, frowned as he stared at Dragosani. He didn’t always declare his earnings from tourism—not all of them, anyway. Finally he said: “I am Kinkovsi, yes, and I do have rooms. But—”

“Well, can I stay here or can’t I?” the other seemed tired now, and impatient. Kinkovsi noted that his clothes, at first glance smart and modern, actually looked crumpled, much-travelled. “I know I’m early by a month, but surely you can’t have that many guests?”

Early by a month! Now Kinkovsi remembered.

“Ah! You must be the Herr from Moscow? The one who made inquiry in April? The one who booked lodgings—but sent no money in advance! Is it you, then, that Herr Dragosani who has the name of the town down the highway? But you are indeed early—though welcome for all that! I shall have to prepare a room for you. Or perhaps I can put you in the English room, for a night or two anyway. How long will you stay?”

“Ten days at least,” Dragosani answered, “if the sheets are clean and the food is at all bearable—and if your Romanian beer is not too bitter!” His glance seemed unnecessarily severe; there was that in his attitude which got Kinkovsi’s back up.

“Mein Herr,” he began with a growl, “my rooms are so clean you could eat off the floor. My wife is an excellent cook. My beer is the best under all the Carpatii Meridionali! What’s more, our manners are good up here—which seems to be more than can be said of you Muscovites! Now, do you want a room or don’t you?”

Dragosani grinned and held out his hand. “I was pulling your leg,” he said. “I like to find out what people are made of. And I like a fighting spirit! You are typical of this region, Hzak Kinkovsi: you wear a farmer’s clothes but you’re a warrior at heart. But me, a Muscovite? With a name like mine? Why, there are some who’d say that you are the foreigner here, ‘Hzak Kinkovsi!’ It’s in your name, your accent, too. And what of your use of ‘Mein Herr’? Hungarian, aren’t you?”

Kinkovsi briefly studied the other’s face, looked him up and down, decided he liked him. The man had a sense of humour, anyway, which in itself made a welcome change. “My grandfather’s grandfather was from Hungary,” he said, taking Dragosani’s hand and giving it a firm shake, “but my grandmother’s grandmother was a Wallach. As for the accent, it’s local. We’ve absorbed a good many Hungarians over the decades, and a good many settled here. Now?—I’m a Romanian no less than you. Only I’m not as rich as you!” He laughed, showing yellow, worn-down teeth in a face of creased leather. “I suppose you’d say I’m a peasant. Well, I’m what I am. As for ‘Mein Herr’—would you prefer me to call you ‘Comrade’?”

“Heavens, no! Not that!” Dragosani answered at once. “‘Mein Herr’ will do nicely, thanks.” He too laughed. “Come on, show me this English room of yours.…”

Kinkovsi led the way from the big Volga to the tall, high-peaked guesthouse. “Rooms?” he grumbled. “Oh, I’ve plenty of rooms, all right! Four to each floor. You can have a whole suite of rooms if you like.”

“One will be fine,” Dragosani answered, “as long as it has its own bath and toilet.”

“Ah—en suite, is it? Well, then, that’s the top floor. A room with its own loo and bath up under the roof. Very modern.”

“I’m sure,” said Dragosani, not too dryly.

He saw that the ground floor walls of the house had been rendered and pebble-dashed on top of the sand-coloured cement. Rising damp, probably. But the upper levels showed their original stone construction. The house must be three hundred years old if it was a day. Very suitable. It took him back in time—back to his roots and beyond them.

“How long have you been away?” Kinkovsi asked, letting him in and showing him to a room on the ground floor. “You’ll have to stay here for now,” he explained, “until I can get the upstairs room ready. An hour or two, that’s all.”

Dragosani kicked off his shoes, hung his jacket over a wooden chair, dropped onto a bed in a disk of sunlight where it came through an oval window. “I’ve been away half of my life,” he said. “But it’s always good to come back. I’ve been back for the last three summers now, and four more to go.”

“Oh? Got your future all planned out, have you? Four more to go? That sounds sort of final. What do you mean by it?”

Dragosani lay back, put his hands behind his head, looked at the other through eyes slitted against the glancing sunlight. “Research,” he finally said. “Local history. At only two weeks each year, it should take me another four years.”

“History? This country is steeped in it! But it’s not your job, then? I mean, you don’t do it for a living?”

“No,” the man on the bed shook his head. �

�In Moscow I’m a mortician.” That was close enough.

“Huh!” Kinkovsi grunted. “Well, it takes all kinds. Right, I’m off now to sort out your room. And I’ll make arrangements for a meal. If you want the loo, it’s just out here in the corridor. Just take it easy.…”

When there was no answer he glanced again at Dragosani, saw that his eyes were closed—the warm sunshine and the quiet of the room. Kinkovsi picked up his guest’s car keys from where he’d tossed them down at the foot of the bed, quietly left the room and eased the door shut behind him. One last glance as he went; the rise and fall of Dragosani’s chest had taken on the slow rhythm of sleep. That was good. Kinkovsi nodded to himself and smiled. Obviously he felt at home here.

* * *

Dragosani chose new lodgings each time he came here. Always in the vicinity of the town he called home—within spitting distance—but not so close to the last place that he’d be remembered from the previous year. He had thought of using an assumed name, a pseudonym, but had thrown the idea out untried. He was proud of his name, probably in defiance of its origin. Not in defiance of Dragosani the town, his geographical origin, but the fact that he’d been found there. As for his parents: his father was that almost impregnable mountain range up there to the north, the Transylvanian Alps, and his mother was the rich dark soil itself.

Oh, he had his own theories about his real parents; what they’d done had probably been for the best. The way he imagined them, they had been Szgany, “Romany,” Gipsies; young lovers out of feuding camps, their love had not had the power to reconcile old slights and spites. But they had loved, Dragosani had been born, and he had been left. As to actually tracking them down, those unknown parents: he had thought to do that three years ago and had come here for precisely that reason. But … it had been utterly hopeless. A task enormous, impossible. There were as many gipsies in Romania now as ever there had been in the old days. Despite their “satellite” designation, old Wallachia, Transylvania, Moldavia and all the land around had retained something of autonomy, of self-determination. Gipsies had as much right to be here as the mountains themselves.

Mad Moon of Dreams

Mad Moon of Dreams Psychosphere

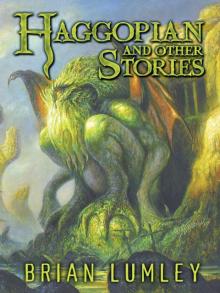

Psychosphere Haggopian and Other Stories

Haggopian and Other Stories Resurgence_The Lost Years_Volume Two

Resurgence_The Lost Years_Volume Two Necroscope: Harry and the Pirates: And Other Tales From the Lost Years

Necroscope: Harry and the Pirates: And Other Tales From the Lost Years Necroscope®

Necroscope® Dreamlands 5: Questers for Kuranes: Two Tales of Hero and Eldin

Dreamlands 5: Questers for Kuranes: Two Tales of Hero and Eldin The Taint and Other Novellas: Best Mythos Tales Volume 1

The Taint and Other Novellas: Best Mythos Tales Volume 1 Necroscope: Defilers

Necroscope: Defilers Beneath the Moors and Darker Places

Beneath the Moors and Darker Places The Fly-By-Nights

The Fly-By-Nights Khai of Khem

Khai of Khem Ship of Dreams

Ship of Dreams The Nonesuch and Others

The Nonesuch and Others Blood Brothers

Blood Brothers Necroscope

Necroscope The Burrowers Beneath

The Burrowers Beneath Bloodwars

Bloodwars No Sharks in the Med and Other Stories

No Sharks in the Med and Other Stories The House of Doors - 01

The House of Doors - 01 Screaming Science Fiction

Screaming Science Fiction Necroscope III: The Source

Necroscope III: The Source Vampire World I: Blood Brothers

Vampire World I: Blood Brothers Iced on Aran

Iced on Aran Necroscope: Invaders

Necroscope: Invaders Necroscope: The Lost Years

Necroscope: The Lost Years Return of the Deep Ones: And Other Mythos Tales

Return of the Deep Ones: And Other Mythos Tales Necroscope V: Deadspawn

Necroscope V: Deadspawn Titus Crow, Volume 3: In the Moons of Borea, Elysia

Titus Crow, Volume 3: In the Moons of Borea, Elysia Hero of Dreams

Hero of Dreams Necroscope IV: Deadspeak

Necroscope IV: Deadspeak The Last Aerie

The Last Aerie The Second Wish and Other Exhalations

The Second Wish and Other Exhalations Necroscope: The Touch

Necroscope: The Touch Necroscope: The Plague-Bearer

Necroscope: The Plague-Bearer Necroscope: Avengers

Necroscope: Avengers Necroscope II: Wamphyri

Necroscope II: Wamphyri Necroscope II_Vamphyri!

Necroscope II_Vamphyri! A Coven of Vampires

A Coven of Vampires Spawn of the Winds

Spawn of the Winds Sorcery in Shad

Sorcery in Shad Deadspawn

Deadspawn Necroscope V: Deadspawn n-5

Necroscope V: Deadspawn n-5 Necroscope: Invaders e-1

Necroscope: Invaders e-1![Beneath the Moors and Darker Places [SSC] Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/beneath_the_moors_and_darker_places_ssc_preview.jpg) Beneath the Moors and Darker Places [SSC]

Beneath the Moors and Darker Places [SSC] Demogorgon

Demogorgon Harry and the Pirates_and Other Tales from the Lost Years

Harry and the Pirates_and Other Tales from the Lost Years Necroscope IV: Deadspeak n-4

Necroscope IV: Deadspeak n-4 Deadspeak

Deadspeak The Taint and Other Novellas

The Taint and Other Novellas Blood Brothers vw-1

Blood Brothers vw-1 The Source n-3

The Source n-3 In the Moons of Borea

In the Moons of Borea Avengers

Avengers Necroscope n-1

Necroscope n-1 Vamphyri!

Vamphyri! Questers for Kuranes: Two Tales of Hero and Eldin

Questers for Kuranes: Two Tales of Hero and Eldin Necroscope II: Wamphyri! n-2

Necroscope II: Wamphyri! n-2 The Source

The Source Elysia

Elysia The Plague-Bearer

The Plague-Bearer The Touch

The Touch Invaders

Invaders Necroscope 4: Deadspeak

Necroscope 4: Deadspeak Compleat Crow

Compleat Crow The Mobius Murders

The Mobius Murders Defilers

Defilers