- Home

- Brian Lumley

Deadspeak Page 11

Deadspeak Read online

Page 11

The white leisure craft was very noticeable now, but still it hovered on the periphery of the espers’ vision, its screw idling where it waited in the deep-water channel. Both of them now held binoculars to their eyes, and Jordan had stood up, was leaning forward against the harbour wall as the Samothraki came chugging into view around the mole.

“Here she comes,” he breathed. “Right between the old boy’s legs!” He sent his telepathic mind reaching across the water, seeking out the minds of the captain and crew. He wanted to know the location of the cocaine … if one of them should be thinking about it right now … or about its ultimate destination …

“What old boy’s legs?” Layard’s voice came to him distantly, even though he was right here beside him. Such was Jordan’s concentration that he’d almost entirely shut out the conscious world.

“The Colossus,” Jordan husked. “Helios. One of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world. That’s where he stood—right there, straddling that harbour mouth—until 224 B.C.”

“So you did read your map after all!” breathed Layard.

The old Samothraki was coming in; the sleek white modern vessel was going out; the former was obscured by the latter as they came up alongside each other—and dropped their anchors.

“Shit!” said Jordan. “Mindsmog again! I can’t see a damn thing through it!”

“I can feel it,” Layard answered.

Jordan swept his glasses along the sleek outline of the white vessel and read off its name from the hull: the Lazarus. “She’s a beauty,” he started to say, and froze right there. Centred in his field of view, the man in black on the foredeck was seated upright in his chair; the back of his head was visible; he was looking at the old Samothraki. But as Jordan fixed him in his binoculars, so that oddly proportioned head turned until its unknown owner was staring straight at the esper across one hundred and twenty yards of blue water. And even though they were both wearing dark glasses, and despite the distance, it was as if they stood face-to-face!

WHAT? a powerful mental voice grunted its astonishment full in Jordan’s mind. A THOUGHT THIEF? A MENTALIST?

Jordan gasped. What the hell did he have here? Whatever it was, it wasn’t what he’d been looking for. He tried to withdraw but the other’s mind closed on his like a great vise … and squeezed! He couldn’t pull out! He flopped there loosely against the harbour wall and looked at the other where he now stood tall—enormous to Jordan—in the shade of the black canopy.

Their eyes were locked on each other, and Jordan straining so hard to look away, redirect his thoughts, that he was beginning to vibrate. It was as if solid bars of steel were shooting out from the other’s hidden eyes, across the water and down the barrel’s of Jordan’s binoculars into his brain; where even now they were hammering at his mind as they drove home their message.

WHOEVER YOU ARE, YOU HAVE ENTERED MY MIND OF YOUR OWN FREE WILL. SO … BE … IT!

Layard was on his feet now, anxious and astonished. For all that he’d experienced little or nothing of the telepath’s shock and, indeed, terror, still he could tell by just looking at him that something was terribly wrong. With his own mind full of mental smog and crackling, buzzing static, he reached to take Jordan’s sagging weight—in time to guide and lower the telepath to the bench as he collapsed like a jelly, unconscious in his arms …

IV: Lazarides

THAT SAME NIGHT:

The Lazarus lay moored to a wharf in the main harbour, entirely still and darkly mirrored in water smooth as glass; three of the four crewmen had gone ashore, leaving only a watchkeeper; the boat’s owner sat at a window seat upstairs in the most disreputable taverna of the Old Town, looking out and down across the waterfront. Downstairs a handful of tourists drank cheap brandy or ouzo and ate the execrable food, while the local layabouts, bums, and rejects in general laughed and joked with them in English and German, made coarse jokes about them in Greek, and scrounged drinks.

There were three or four blowsy-looking English girls down there, some with Greek boyfriends, all the worse for wear and all looking for the main chance. They danced or staggered to sporadic bursts of recorded bouzouki music, and later would dance more frantically, gaspingly, horizontally, to the accompaniment of slapping, sweating, ouzo-smelling flesh.

Upstairs was out of bounds to such as these, where the owner of the taverna carried out the occasional shady deal, or perhaps drank, talked, or played cards with some of his many shady friends. None of these were around tonight, however, just the landlord himself, and a young Greek whore sitting alone in the alcove leading to her business premises—a small room with a bed and washbasin—and the man who now called himself Jianni Lazarides, occupying his window seat.

The fat, stubble-chinned proprietor, called Nichos Dakaris, was here to serve a bottle of good red wine to Lazarides, and the girl was here because she had a black eye and couldn’t ply her trade along the waterfront. Or rather, she wouldn’t. It was her way of paying Dakaris back for the beatings he gave her whenever he was obliged to cough up hush money to the local constabulary for the privilege of letting a prostitute use his place. If not for the fact that he felt the urge himself now and then, he probably wouldn’t let her stay here at all; but she paid for her room “in kind” once or twice a week as the mood took Dakaris, on top of which he got forty percent of her take. Or would get it if she only used her room and wouldn’t insist on free-lancing in Rhodian back alleys! Which was his other reason for beating her.

As for Jianni Lazarides: he also had his reasons for being here. This was the venue for his meeting with the Greek “captain” of the Samothraki and a couple of his cohorts, when he would look for an explanation as to how and why someone had been selling tickets for their assumed “covert” drug-running operation. Actually he already knew why, for he’d had it from the mind of Trevor Jordan; but now he wanted to hear it from Pavlos Themelis himself, the Samothraki’s master, before deciding how best to detach himself from the affair.

For Lazarides had put good money into this allegedly safe business (which now appeared to be anything but safe), and he wanted his money back or … payment in kind? For money and power were gods here in this era no less than in all the foregone centuries of human avarice, of which Lazarides had more than an obscure knowledge. And indeed there were easier, safer, more guaranteed ways to make and use money in this vastly complex world; ways which would not attract the attention of its lawkeepers, or at any rate not too much of it.

Money was very important to Lazarides, and not just because he was greedy. This world he’d emerged into was overcrowded and threatening to become even more so, and a vampire has his needs. In the old times a boyar would be given lands by some puppet prince or other, to build a castle there and live in seclusion and, preferably and eventually, something of anonymity. Anonymity and longevity had walked hand in hand in the old days; you could not have one without the other; a famous man must not be seen to live beyond his or any other ordinary creature’s span of years. But in those days news travelled slowly; a man could have sons; when he “died,” there would always be one of those ready and waiting to step into his shoes.

Likewise in the here and now, except that news and indeed men no longer travelled slowly, because of which the world was that much smaller. So … how then to build an aerie, and all unnoticed, in these last dozen years of this twentieth century? Impossible! But still a very rich man could purchase obscurity, and with it anonymity, and so go about his business as of old. Which begged a second question: how to become very rich?

Well, Janos Ferenczy thought he had answered that one more than four hundred years ago, but now in the guise of Lazarides he wasn’t so sure. In those days a gem-encrusted weapon or large nugget of gold had been instant wealth. Now too, except that now men would want to know the source of such an item. In those days a boyar’s lands and possessions—or loot—had been his own, no questions asked. And only let him who dared try to take them away! But today such baubles as a jewelled hi

lt or a solid gold Scythian crown were “historic treasures,” and a man may not trade with them without first satisfying a good many—far too many—queries as to their origin.

Oh, Janos knew the source of his wealth well enow; indeed, here it sat in this window seat, overlooking a harbour in the once powerful land of Rhodos! For the very man who “discovered” and unearthed these treasures in the here and now was the selfsame one who buried them deep in the earth more than four hundred years ago! How better to prepare for a second coming into the world, when one has foreseen a long, long period of uttermost dark?

And having retrieved these several caches, these items of provenance put down so long ago, surely it would be the very simplest thing to transfer them into land, properties of his own, the territories and possessions of a Wamphyri Lord? Oh, true, an aerie was out of the question, even a castle … but an island? An island, say, in the Greek sea, which had so many?

Ah, if only it could have been that easy!

But places change, nature takes her toll, earthquakes rumble and the land is split asunder, and treasures are buried deeper still where old markers fall or are simply torn down. The mapmakers then were not nearly so accurate, and even a keen memory—the very keenest vampire memory—will fade a little in the face of centuries …

Janos sighed and glanced out of the window at the harbour lights, and at those measuring the leagues of ocean, lighting their ships like luminous inchworms far out on the sea. The odious proprietor had gone now, back downstairs to serve ouzo and watered-down brandy and count his takings. But the bouzouki music still played amidst bursts of coarse laughter, the would-be lovers still danced and groped, and the young whore remained seated in her alcove as before.

The hour must be ten, and Janos had said he would contact his American thrall about then. Well, and he would … in a while, in a while.

He poured a little wine for himself, good and deep and red, and watched the way his glass turned to blood. Aye, the blood was the life—but not in a place like this! He would sup when he would sup, and meanwhile the wine could ease his parch. What was it after all but the plaguey unending thirst of the vampire, which one must either tame or die for? Or at least, tame within certain limits … And Janos wasn’t shrivelled yet.

The whore had heard the chink of his glass against the bottle. Now she looked across, her surly mouth pouting; she, too, had a glass, which was empty.

Janos felt her eyes on him and turned his head. Across the room she took note of his straight-backed height, dark good looks, and expensive clothing, and wondered at the dark-tinted spectacles which shielded his eyes. But at the distance she could not see how coarse and large-pored was his skin, how wide and fleshy his mouth, or the disproportionate length of his skull, ears, and three-fingered hands. She only knew that he looked powerful, detached, deep. And certainly he was not a poor man.

She smiled, however unprettily, stood up, and stretched—which had the desired effect of lifting her pointed breasts—and crossed to Janos’s window seat. He watched her swaying towards him and thought, Of your own free will!

“Will you drink it all?” she asked him, cocking a knowing eyebrow. “All to yourself … all by yourself?”

“No,” he said at once, his expression remaining entirely ambivalent, “I require very little … of this.”

Perhaps his voice surprised her: it was a growl, a rumble, so deep it made her bones shiver. And yet she didn’t find it displeasing. Still, its force was sufficient that she took a pace to the rear. But as she drew back, so he smiled, however coldly, and indicated the bottle. “Are you thirsty, then?”

Was he a Greek, this man? He knew the tongue, but spoke it like they did in some of the old mountain villages, which modern times and ways would never reach. Or perhaps he wasn’t Greek after all; or maybe he was, but many times removed, by travel and learning and the exotic dilution of far, foreign parts.

The girl didn’t normally ask, but now she said, “May I?”

“By all means! As I have said, my real requirements lie in another direction.”

Was that a hint? He must know what she was, surely? Should she invite him through the alcove and into her curtained room? Then, as she filled her glass … it was as if he had read her mind!—though of course that wouldn’t be too difficult. “No,” he said, with a slight but definite shake of his great head. “Now you must leave me alone. There are matters to occupy my mind, and friends will soon be joining me here.”

She threw back her wine, and smiling, he refilled her glass before repeating, “Now go.”

And that was that; the command was irresistible; she returned to her bench under the alcove. But now she couldn’t keep her eyes off him. He was aware of it but it didn’t seem to bother him. If he had not commanded her attention, then he might feel concerned.

Anyway, it was now time for Janos to discover what Armstrong was doing. He put the girl out of his mind, reached out with his vampire senses along the waterfront to the mole, and into the shadows there where massive walls reached up out of the still waters. No bright lights there, just heaps of mended nets, lobster pots, and the floats and amphoraelike vases with which the fishermen caught the octopus. And the ever-faithful Armstrong, of course, waiting for his master’s commands.

Do you hear me, Seth?

“I’m here, where I should be,” Armstrong whispered into the shadows of the mole, as if he talked to himself. He made no mention of the hunger, which Janos could feel in his mind like an ache. That was good, for a master’s needs must always come first; but at the same time a man should not forget to reward a faithful dog. Armstrong would receive his reward later.

I now seek out the mentalist, the Englishman, Janos briefly explained, and him I shall send to you. The other English will doubtless accompany him. That one is not required, for he can only hinder my works. One of them can tell us as much as two. Do you understand?

Armstrong understood well enough—and again Janos felt the hunger in him. So much hunger that this time he commanded, You will neither mark him nor take anything from him—nor yet give him anything of yourself! Do you hear me, Seth?

“I understand.”

Good! I suggest that he receive a stunning blow—say, to the back of the neck?—and that he then fall in the water where it is deep. Look to it, then, for if all is well, I shall send them to you soon.

Without more ado he then sent his vampire senses creeping amidst the bright lights of the New Town, searching among the hotels and tavernas, in and around the bars, fast-food stalls, and nightclubs. It was not difficult; the minds he sought were different, possessed some small powers of their own. And one of them at least had already been penetrated, damaged, almost destroyed. Indeed it was going to be destroyed, but not just yet. Time enough for that when Janos knew all that it knew. And from the single glimpse he had stolen before crushing down on that mind and driving it to seek sanctuary in oblivion, he was certain that it knew a great deal.

The mind of a mentalist, aye … a “telepath,” as they called them now. But if Janos had caught the thought-thief spying on him (or if not on him directly, at least spying on the drug-running operation of which he was a part), how much then had he discovered before he was caught? Enough to make him dangerous, be sure! For in the moment of shutting him down Janos had sensed that the mindspy knew what he was! And that must never be. What? To be discovered as a vampire here in this modern world? Oh, some might scoff at such a suggestion—but others would not. This mentalist was just such a one, and there’d been echoes in his mind which hinted he knew of others. An entire nest of them!

Janos detected and seized upon a wave of frightened thoughts. He knew the scent of them. It was a mind he had encountered before, recently, which like a familiar face he now recognised. Terrified, cringing thoughts they were, bruised and battered to mental submission—but rising now once more to consciousness. He tracked them like a bloodhound, and entering that shuddering mind knew at once that this was the one and he’d made n

o mistake …

Ken Layard attended Trevor Jordon in the latter’s hotel room. Their single rooms were side by side, with access from a corridor. For twelve hours solid the telepath had lain here now: six of them as still as a corpse, under the influence of a powerful sedative administered by a Greek doctor, four more in what had seemed a fairly normal sleeping mode, and the rest tossing and turning, sweating and moaning in the grip of whatever dream it was that bothered him. Layard had tried to wake him once or twice, but his friend hadn’t been ready for it. The doctor had said he’d come out of it in his own good time.

As for what the trouble was: it could have been anything, according to the doctor. Too much sun, excitement, drink—a bug which had got into his system, perhaps? Or a bad migraine—but nothing to worry about just yet. The tourists were always going down with something or other.

Layard turned away from Jordan’s bed, and in the next moment heard his friend say, “What? Yes—yes—I will.” He spun on his heel, saw Jordan’s eyes spring open, watched him push himself upright into a seated position.

There was a jar of water on Jordan’s bedside table; Layard poured him a glass and offered it to him. Jordan seemed not to see it. His eyes were almost glazed. He swung his legs out of the bed, reached for his clothes where they were draped over a chair. The locator wondered: Is he sleepwalking?

“Trevor,” he quietly said, taking his arm, “are you … ?”

“What?” Jordan faced him, blinked rapidly, suddenly looked him full in the face. His eyes focused and Layard guessed that he was now fully conscious, and apparently capable. “Yes, I’m okay. But …”

“But?” Layard prompted him, while Jordan continued to dress himself. There was something almost robotic about him.

The telephone rang. As Jordan went on dressing, Layard answered it. It was Manolis Papastamos, wanting to know how Jordan was doing. The Greek lawman had come on the scene only seconds after Jordan’s collapse; he’d helped Layard get him back here and called in the doctor.

Mad Moon of Dreams

Mad Moon of Dreams Psychosphere

Psychosphere Haggopian and Other Stories

Haggopian and Other Stories Resurgence_The Lost Years_Volume Two

Resurgence_The Lost Years_Volume Two Necroscope: Harry and the Pirates: And Other Tales From the Lost Years

Necroscope: Harry and the Pirates: And Other Tales From the Lost Years Necroscope®

Necroscope® Dreamlands 5: Questers for Kuranes: Two Tales of Hero and Eldin

Dreamlands 5: Questers for Kuranes: Two Tales of Hero and Eldin The Taint and Other Novellas: Best Mythos Tales Volume 1

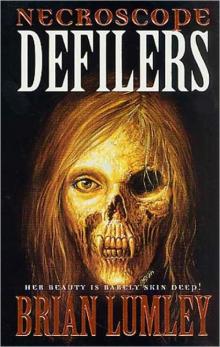

The Taint and Other Novellas: Best Mythos Tales Volume 1 Necroscope: Defilers

Necroscope: Defilers Beneath the Moors and Darker Places

Beneath the Moors and Darker Places The Fly-By-Nights

The Fly-By-Nights Khai of Khem

Khai of Khem Ship of Dreams

Ship of Dreams The Nonesuch and Others

The Nonesuch and Others Blood Brothers

Blood Brothers Necroscope

Necroscope The Burrowers Beneath

The Burrowers Beneath Bloodwars

Bloodwars No Sharks in the Med and Other Stories

No Sharks in the Med and Other Stories The House of Doors - 01

The House of Doors - 01 Screaming Science Fiction

Screaming Science Fiction Necroscope III: The Source

Necroscope III: The Source Vampire World I: Blood Brothers

Vampire World I: Blood Brothers Iced on Aran

Iced on Aran Necroscope: Invaders

Necroscope: Invaders Necroscope: The Lost Years

Necroscope: The Lost Years Return of the Deep Ones: And Other Mythos Tales

Return of the Deep Ones: And Other Mythos Tales Necroscope V: Deadspawn

Necroscope V: Deadspawn Titus Crow, Volume 3: In the Moons of Borea, Elysia

Titus Crow, Volume 3: In the Moons of Borea, Elysia Hero of Dreams

Hero of Dreams Necroscope IV: Deadspeak

Necroscope IV: Deadspeak The Last Aerie

The Last Aerie The Second Wish and Other Exhalations

The Second Wish and Other Exhalations Necroscope: The Touch

Necroscope: The Touch Necroscope: The Plague-Bearer

Necroscope: The Plague-Bearer Necroscope: Avengers

Necroscope: Avengers Necroscope II: Wamphyri

Necroscope II: Wamphyri Necroscope II_Vamphyri!

Necroscope II_Vamphyri! A Coven of Vampires

A Coven of Vampires Spawn of the Winds

Spawn of the Winds Sorcery in Shad

Sorcery in Shad Deadspawn

Deadspawn Necroscope V: Deadspawn n-5

Necroscope V: Deadspawn n-5 Necroscope: Invaders e-1

Necroscope: Invaders e-1![Beneath the Moors and Darker Places [SSC] Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/20/beneath_the_moors_and_darker_places_ssc_preview.jpg) Beneath the Moors and Darker Places [SSC]

Beneath the Moors and Darker Places [SSC] Demogorgon

Demogorgon Harry and the Pirates_and Other Tales from the Lost Years

Harry and the Pirates_and Other Tales from the Lost Years Necroscope IV: Deadspeak n-4

Necroscope IV: Deadspeak n-4 Deadspeak

Deadspeak The Taint and Other Novellas

The Taint and Other Novellas Blood Brothers vw-1

Blood Brothers vw-1 The Source n-3

The Source n-3 In the Moons of Borea

In the Moons of Borea Avengers

Avengers Necroscope n-1

Necroscope n-1 Vamphyri!

Vamphyri! Questers for Kuranes: Two Tales of Hero and Eldin

Questers for Kuranes: Two Tales of Hero and Eldin Necroscope II: Wamphyri! n-2

Necroscope II: Wamphyri! n-2 The Source

The Source Elysia

Elysia The Plague-Bearer

The Plague-Bearer The Touch

The Touch Invaders

Invaders Necroscope 4: Deadspeak

Necroscope 4: Deadspeak Compleat Crow

Compleat Crow The Mobius Murders

The Mobius Murders Defilers

Defilers